Belarus

BelarusЖыццё пад сталом

Напярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

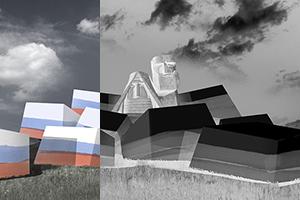

20 December 2023 “Diorama”, Georgian Military Road; architect: Giorgi Chakhava, artists: Zurab Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, Nodar Malazonia, 1983© Nini Palavandishvili

“Diorama”, Georgian Military Road; architect: Giorgi Chakhava, artists: Zurab Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, Nodar Malazonia, 1983© Nini Palavandishvili

Dealing with the Soviet legacy is one of the most critical problems of Georgian culture and politics. Nini Palavandishvili, curator and researcher, demonstrates, on the example of Soviet Georgian mosaics, how the desire to get rid of the Soviet heritage coupled with the neoliberal economic policy leads to the destruction of the cultural heritage, which is a part of Georgian and World cultural heritage.

ქართული English Русский

My interest in the Georgian monumental-decorative mosaics of the Soviet period is a result of the intense changes in public space during the last thirty years. This field of art is an integral part of the urban environment. Still, unlike other fields of art, Soviet-time mosaics were not appreciated in Georgia and are very often a target of aggressive intervention. Georgia’s emotional desire is to detach from the recent past and erase Soviet-time history from the visual memory. Still, the politics of dealing with the Soviet legacy are hardly meaningful. Like other post-Soviet and post-socialist countries, Georgia impatiently tried to forget its former ideology. The neoliberal policies of the Georgian government have led to the unsystematic transformation of our urban environment and the reduction of civic participation in public spaces. Interventions made by non-professionals in shaping the appearance of the city, the “beautification” of the facades, resulted in the gradual destruction of mosaics.

The wide popularization of monumental art in the Soviet Union began during Brezhnev’s rule (1964–1982), as his predecessor, Nikita Khrushchev, advocated for functional and cost-effective construction and forbade the use of decorative elements.

In Georgia, as in most post-Soviet countries, 20th-century mosaics were associated with the Soviet regime and regarded as propaganda tools. From the 1960s, public and residential buildings and educational, cultural, administrative, and industrial facilities in Soviet cities were often decorated with state-commissioned mosaic panels. The facility’s function largely determined the particular theme of the mosaic; mosaics on the facades of industrial buildings, research and educational institutions glorified technological and scientific progress and labour and illustrated the relevant activities. Complementary, these panels served as advertising banners for these buildings and their functions.

Although socialist realism was the only recognized form of Soviet art, if we refer to Stalin’s famous formula, in soviet Georgia, the national form often prevailed over the socialist content. Although the artists working in the Soviet period were obliged to act according to the principles of realism and mosaic was considered a “product of the regime,” they were distinguished by their national forms and national characteristics and translated the common values into the local visual language. As a result, the iconography of Soviet Georgian mosaics offers a wide style range: from social realism to futurism and from minimalist graphic paintings saturated with national motifs and themes to complex compositions and even to abstractionism. Although the Soviet regime did not recognize the latter until the very end of its existence, such works are frequent in Soviet Georgian monumental art.

Former swimming pool Laguna Vere, Tbilisi; artist: Koka Ignatov, 1978© Gogita Bukhaidze

Former swimming pool Laguna Vere, Tbilisi; artist: Koka Ignatov, 1978© Gogita BukhaidzeThe first Soviet mosaics in Georgia can be found on the territory of the former Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy (VDNH in Russian) in Tbilisi, currently Expo Georgia. Five mosaic pieces created between 1961 and 1963 illustrate the content and stylistic variety I mentioned above. Starting with Guram Kalandadze’s graphic and minimalist mosaics, there is Leonardo Shengelia’s glorification of technological progress, Aliko Gorgadze’s and Tezo Asatiani’s socialist realist panel with national motifs, and Kukuri Tsereteli’s abstract graphic compositions.

Former Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy, Tbilisi; artists: Guram Kalandadze, Leonardo Shengelia, Aliko Gorgadze and Tezo Asatiani, 1960s© Gogita Bukhaidze

Former Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy, Tbilisi; artists: Guram Kalandadze, Leonardo Shengelia, Aliko Gorgadze and Tezo Asatiani, 1960s© Gogita BukhaidzeSome years later (1968–69), Vakhtang Kokiashvili created “The Khevsurian Wedding” for the Georgian Pavilion at the Moscow Exhibition Center. Although Giotto’s “Kiss of Judas” undoubtedly inspires the artistic expression of this panel, the artist was adept at translating Giotto’s particular horizontal composition, facial features, and other elements into a mosaic panel and giving it a unique national character.

The Khevsurian Wedding, artist: Vakhtang Kokiashvili, 1968-69© Nini Palavandishvili

The Khevsurian Wedding, artist: Vakhtang Kokiashvili, 1968-69© Nini PalavandishviliDespite these early examples, the decoration of the Bichvinta resort complex, built in 1959–67, is considered the origin of 20th-century mosaics in Georgia. The indoor and outdoor mosaics of the Bichvinta resort complex made by Zurab Tsereteli are among the largest in size and quantity. Tsereteli deserves particular attention: One of the most successful artists in the entire Soviet Union produced mosaic smalti tiles in his workshop, while Soviet Georgia mainly imported this material from Ukraine and the Baltic countries. Most importantly, the Soviet Georgian artist managed that his mosaic works escape the restraints of socialist realism. They do not show characters typical of Soviet art, workers, or heroes of labour or war. Instead, they display Fairy-tale and mythological figures and abstract motifs and invite people weary of daily work into another imaginary fairy-tale world.

The iconography of Georgian mosaics is a clear example of how the standards set for mosaic characters and themes, mainly related to various labour achievements, technological progress, and the protection of national traditions, were discussed at the local level in Georgia, far from the regulatory centre. The Union of Artists of Georgia and the production unit subordinated to it made the decisions on the execution of the mosaics. As a result, Georgian mosaics rarely feature Soviet symbols, such as the hammer and sickle, or Soviet leaders – only a few red stars, and CCCP (USSR in Russian) here and there in small letters.

Technological progress, especially space exploration in the 1960s, is another popular topic of the soviet mosaics. The flights of Yuri Gagarin in 1961 and Valentina Tereshkova in 1963 caused great excitement. Space became the principal symbol of Soviet achievements. Accordingly, a vast number of mosaics feature astronauts and spaceships. Of particular interest are two mosaics at different locations in Tbilisi, both by unidentified artists. One of the mosaics decorates the former furniture factory “Gantiadi.” The female astronaut figure is a replica of the 12th-century portrait of Queen Tamar from the Vardzia fresco. Considering the importance of Queen Tamar for the Georgian nation, it should not be surprising that the artist chose her image as a symbol of a strong Soviet woman. The second mosaic is on a decorative wall in a small square in the Varketili district. The female astronaut figure resembles the image of Anna Lee Fisher, the first mother in space, depicted on the cover of LIFE magazine in 1985. Anna Lee Fischer was never well-known in Soviet Georgia. However, it is possible that in the late 1980s, when the Soviet Union was on the way to falling apart, more foreign press was coming in, and thus artists had access to more material.

Former furniture factory “Gantiadi”, Tbilisi; author unknown, 1970s© Gogita Bukhaidze

Former furniture factory “Gantiadi”, Tbilisi; author unknown, 1970s© Gogita Bukhaidze Tbilisi, author unknown, 1980s© Gogita Bukhaidze

Tbilisi, author unknown, 1980s© Gogita BukhaidzeThe iconography of mosaics on cultural and educational facilities, as well as on smaller structures, is saturated with national symbols and/or depicts domestic heroes and fables. For example, a decorative panel with a hunting scene by Kukuri Tsereteli on Gulia Square in Tbilisi shows a scene from Shota Rustaveli’s “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin.” The exact date of its creation is unknown, but most likely, it was dedicated to Shota Rustaveli’s 800th anniversary, celebrated in 1966. Nugzar Medzmariashvili’s mosaic in the reading hall of the National Science Library in Tbilisi is based on the motifs of the Prometheus myth. In Georgian mythology, Prometheus has a “twin brother,” Amirani, who symbolizes the Georgian nation, its hardships, and its struggle for survival.

“Hunting”, Tbilisi; Artist: Kukuri Tsereteli, 1960s© Nini Palavandishvili

“Hunting”, Tbilisi; Artist: Kukuri Tsereteli, 1960s© Nini PalavandishviliAn interesting example is the “Diorama,” a memorial dedicated to the Treaty of Georgievsk (between Georgian King Irakli II. and Russian empress Catharina II in 1873) on the Georgian Military Road (architect: Giorgi Chakhava, artists: Zurab Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, Nodar Malazonia). The central figure of the large-scale composition is a mother with a child, where the authors iconographically paraphrase Virgin with the Child. Around the central figure are depictions of Georgian and Russian literary and historical characters.

“Diorama”, Georgian Military Road; architect: Giorgi Chakhava, artists: Zurab Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, Nodar Malazonia, 1983© Nini Palavandishvili

“Diorama”, Georgian Military Road; architect: Giorgi Chakhava, artists: Zurab Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, Nodar Malazonia, 1983© Nini PalavandishviliThe artists’ collective developed a particular technique. They have applied the traditional Georgian cloisonné enamel to monumental works and used special tinted and burnt glass, different from Smalti. Using the same technique, they decorated a bus stop in Tsikhisdziri and a tea pavilion in Kutaisi.

Despite the regional location, the national symbol most frequently encountered in Georgian mosaic art is the vine and grapes. Medieval artists considered it a symbol of the Virgin Mary; accordingly, Georgian church architecture and iconography frequently featured it as an ornament. In contrast, Soviet iconography translated vine and grapes into national agricultural symbols. While religious symbols were not encouraged during the Soviet regime, beginning in the early 1980s, as the system started to weaken and signs of nationalism emerged in various republics, church images began to find broader acceptance in mosaic iconography. However, as a socio-cultural place, the church has always played an important role, even in Soviet Georgia and was; the leading tourist destination.

“Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani”, Bolnisi; artist: Vazha Mishveladze, 1984© Gogita Bukhaidze

“Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani”, Bolnisi; artist: Vazha Mishveladze, 1984© Gogita Bukhaidze Former tea factory, Batumi; author and year unknown© Nini Palavandishvili

Former tea factory, Batumi; author and year unknown© Nini PalavandishviliThe pavilion-type bus stops, designed by architect Giorgi Chakhava in collaboration with Zurab Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, and Nodar Malazonia in Abkhazia, deserve particular mention. In recent years, numerous photo books have been dedicated to the architecture of bus stops in the former Soviet Union. However, the bus stops scattered along the Black Sea coast in Abkhazia are particularly noteworthy. Nothing comparable to them has been created in the Soviet Union either before or since; they are an expression of imagination free from ideology. Furthermore, these functional pavilions of thin shell structures indicate their authors’ engineering and artistic mastery and prove the high quality of those mosaics; moreover, none of them repeats the shape or composition of another.

Bus stop “Elephant”, Alakhadzi; architect: Giorgi Chakhava, artists: Zurab Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, Nodar Malazonia,1970s© Giorgi Chakhava family archive

Bus stop “Elephant”, Alakhadzi; architect: Giorgi Chakhava, artists: Zurab Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, Nodar Malazonia,1970s© Giorgi Chakhava family archiveToday, these pavilions and most buildings decorated with mosaics have lost their original function and are abandoned. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, this field of art was particularly neglected, mainly due to the country’s economic condition after the fall of the Soviet Union. Long carelessness caused the existing mosaics’ gradual damage. As I mentioned earlier, the neglect of mosaics is related to the attempt to completely erase the legacy of the Soviet past from cultural or visual memory. On the other hand, even more violently, mosaics are affected by the neoliberal policy of the Georgian government, mainly through the privatization of abolished or partially functioning industrial buildings in the cities and the gradual destruction of those in the regions. Most facilities in Georgia with mosaic works are now privately owned. The Georgian state did not impose regulations on how to treat and preserve mosaics on new owners. The owners themselves, with rare exceptions, do not see any value in these works and do nothing to preserve them. Unfortunately, time, private interests, and nihilism extinguished many essential artworks. As a result following buildings and mosaics were destroyed: restaurant Aragvi and its decoration, as well as those at the Lagidze Waters shop, Hydro-Meteorological Institute, Rustaveli subway entrance, and Institute of Metallurgy in Tbilisi; the decorative walls in the Benze settlement and the Tobacco Factory in Batumi; and the Khashuri haberdashery factory, on the Rustavi autodrome, on the Agrarian University and Sanatorium “Kolkhida” in Mtsvane Kontskhi, Zestafoni Ferroalloys plant, Tsalenjikha tea factory, and many other mosaics, were destroyed as a result of the demolishing the buildings that remained non-functional.

After years of struggle, protests, and petitions, renovation works have been initiated on a former café “Fantasia” in Batumi (1980), which is known as the “Octopus.” Giorgi Chakhava, in cooperation with Zurab Kapanadze, designers of Cafe “Fantasia” in Batumi (1980) used the same thin shell structure as in the bus stops on the Black Sea coast. However, the size (250 sq m) of the “Octopus” exceeds the bus stops, and is more complex. This architectural structure has a form of an octopus surrounded by sea creatures – fish, dolphins, seahorses, eels, etc. Shape and colourfulness of the “Octopus” immediately draw attention, but it is also in harmony with the environment. The “Octopus” was distinguished not only by its artistic value but also by its engineering significance. Innovative for that time, the authors incorporated a cold water distribution system into the construction. During hot summer days, cold water sprayed out from the sea creatures sitting on the “Octopus,” cooling the surface of the building and its surroundings.

Café “Fantasia”, Batumi; architect: Giorgi Chakhava, artists: Zurab Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, Nodar Malazonia, 1975© Gogita Bukhaidze

Café “Fantasia”, Batumi; architect: Giorgi Chakhava, artists: Zurab Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, Nodar Malazonia, 1975© Gogita BukhaidzeSince the late 1990s, the “Octopus” in Batumi had been abandoned, and its condition had gradually deteriorated. Several unsuccessful attempts have been made to list the structure as an immovable monument of cultural heritage. The turning point came in 2014, when there was a risk of demolishing it; however, the population of Batumi and of Georgia managed to save it through protests and petitions. In 2017, Batumi municipality finally started restoration works on the structure. Financed through a private fund, Cartu, the restoration was commissioned to a company with no experience in restoration work. After three years of work, the “Octopus” reemerged with an altered appearance – distorted original forms and designs, with totally new smalti of different sizes and colours, and without the water-cooling system. In 2020, the new “Octopus” even proved to be worthy of being listed as a monument of cultural heritage.

Café “Fantasia”, Batumi; after renovation, 2020© Tamri Bziava

Café “Fantasia”, Batumi; after renovation, 2020© Tamri BziavaTwo years earlier, in 2018, three stops designed by Giorgi Chakhava were granted the status of monuments of cultural heritage for their architectural value. Mosaic panels of the artistic group of Kapanadze, Lezhava, and Malazonia decorate all three stops. However, despite being given heritage status, the structures still need to be consolidated, the mosaics still need to be cleaned, and professional conservation has yet to be initiated.

In August 2020, a photo circulated on social networks showing an already damaged Soviet mosaic on the territory of the companies Mitana and Tkbili Kvekana in Tbilisi. Railings and iron gates were cut into parts of the mosaic. Commenting on the incident, an official of the Agency of Monuments Protection of Georgia stated: “The mosaics, which are quite numerous, still need to be studied independently and their status determined, which is why legal mechanisms do not apply to some of them that do not have status. Undoubtedly, a better legal mechanism is needed to protect similar works of culture.”

In 2021, the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Youth of Georgia announced a competition for the registration/restoration of endangered 20th-century mosaics in Georgia. The competition aimed to protect and preserve monumental and decorative art examples. At that time, mosaics had already been recorded and mapped. Still, the authors of the existing documentation didn't win the competition. Instead, the newly established Ribirabo Foundation spent 40,000 GEL allocated to create a new website and an app for the project.

In 2021, another mosaic-adorned stop created by the Chakhava, Kapanadze, Lezhava, and Malazonia collective, this time in Tsikhisdziri, was granted monument status as a cultural heritage site. The Ministry of Culture and Monuments Protection of Georgia financed the mosaic restoration, to be carried out by the Ribirabo Foundation. Although despite the recommendations of experts, the bus stop should be consolidated and the mosaic preserved first and then restored, the foundation and the ministry chose the reversed order of action. As a result, the bus stop structure still needs to be consolidated, and the new mosaic tiles are stored in the Ribirabo workshop.

Bus stop, Tsikhisdziri; architect: Giorgi Chakhava, artists: Zurab Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, Nodar Malazonia, 1970s© Gogita Bukhaidze

Bus stop, Tsikhisdziri; architect: Giorgi Chakhava, artists: Zurab Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, Nodar Malazonia, 1970s© Gogita BukhaidzeIn 2021, the marketing department of the Tbilisi City Hall commissioned and published a tourist map and flyer from the series “Tbilisi Landmarks” dedicated to the 20th-century mosaics. One of the mosaics included in this catalogue is the one on the former Mion scientific research institute. In 2022, the private owner of Mion applied to the Tbilisi City Hall for permission to cut window openings through the mosaic facade of the building; based on a positive response, he proceeded with the work. Although the Mion mosaic legally did not have the status of cultural heritage, it was de facto recognized as a landmark in the documentation published by City Hall. Only after civil society and the press drew attention to the damage to the mosaic did the Tbilisi City Hall become “concerned” and state a wish to restore the mosaic, which it had permitted to damage.

Former research institute for microtechnology "Mioni", Tbilisi; artist: Kukuri Tsereteli, 1970s© Gogita Bukhaidze

Former research institute for microtechnology "Mioni", Tbilisi; artist: Kukuri Tsereteli, 1970s© Gogita BukhaidzeThere needs to be coordination between the Ministry of Culture of Georgia and Tbilisi City Hall’s marketing, culture, and architectural departments. The problem is the need for more legislation to protect the state-owned and privately-owned mosaics scattered across the country. The most efficient and beneficial at this stage would be to categorize the documented mosaics, evaluate them by their historical, artistic, cultural, social, and technical value, and assign the status of monuments of cultural heritage to the selected works. Categorization done by professionals in the field in cooperation with governmental bodies is the only way to protect any work, as a work of cultural heritage will always be on the weak side in the struggle with private interest and profit. Even one case of preserving a similar work or being held accountable for the damage would set a precedent to prevent the destruction of mosaics in the future.

At the same time, the country, whose economic income is largely based on tourism, should understand that art is one of the essential branches of tourism. The recent trend proves that the art of the Soviet or socialist period has gained wide recognition and interest worldwide. The world started to see post-Soviet space and its history in a new way. Soviet history is a small part of Georgian history, and mosaic art belongs to the great cultural heritage that Georgia can be proud of.

Belarus

BelarusНапярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusOn the eve of the unknown the Belarusian writer is playing with the past

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusIm Angesicht der ungewissen Zukunft spielt eine belarussische Schriftstellerin mit der Vergangenheit

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusНакануне Неизвестного беларуская писательница играет с Прошлым

20 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaՌուսաստանն օգտագործել է Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի հակամարտությունը որպես իր աշխարհաքաղաքական շահերն առաջ մղելու սակարկության առարկա

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaRussia used the Karabakh conflict as a bargaining chip to advance its geopolitical interests

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaWie Russland im Spiel um seine eigenen geopolitischen Interessen den Berg-Karabach-Konflikt als Trumpf nutzte

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaКак карабахский конфликт стал разменной монетой в российских геополитических играх

12 December 2023 Georgia

Georgiaამბავი ქართული პოსტკონსტრუქტივიზმისა

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaThe history of Georgian post-constructivism

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaDie Geschichte des georgischen Postkonstruktivismus

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaИстория грузинского постконструктивизма

11 December 2023