Belarus

BelarusЖыццё пад сталом

Напярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 © Har Toum

© Har Toum

The decades-long ongoing Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, including the First Karabakh War of the 1990s and the Second Karabakh War of 2020, the months-long blockade of Artsakh, and finally, the ethnic cleansing of the Armenian population in Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023, necessitated a rethinking of the transformative politics of memory in Armenia. In her essay for OSTWEST MONITORING, cultural anthropologist and author of fiction books Lusine Kharatyan, reflects on collective memory and monuments recounting the tragic events that shocked millions of Armenians. Lusine Kharatyan’s literary work marks a peculiar anthropological turn in contemporary Armenian prose. The author, an active member of PEN Armenia, was shortlisted for the European Union Prize for Literature in 2021 and 2023. One of the events at the Frankfurt Book Fair 2023 was dedicated to her prose, particularly her latest novel “Syriavep” (A Syrian Affair).

Հայերեն English Deutsch Русский

To Lusine that was yesterday

#America_place 21

That night alarm again. And me, in pajamas, in an overcoat hastily put on with the buttons unfastened around my belly, my bare feet in boots. Who is cooking at this late hour? The firefighters walk in and out quickly. This time there is smoke, too. I freeze and shrink. I hug my belly with my hands to protect it from the cold. Akram, my Azeri classmate, is in front of me. He is constantly pacing. In his slippers. Carelessly wearing a short jacket and tightly holding a briefcase. He keeps all his documents in one place, so if he ever needs to quickly run away he knows exactly where his documents are and doesn't need to look for them. He laughs. He says he inherited this habit from his mother; when they fled from Aghdam they did not manage to take anything. And this caused problems for many years afterward. They could not leave the country: they had no documents. And now, in this center-of-the-world America, from where people do not flee, he knows what is important. In life. Especially when there is a need to flee. Perhaps his homeland is the briefcase with documents. [1]

Sunny October; morning. You walk briskly on Sayat Nova, almost like a soldier. But not a displaced person. Dis-placed. The place. By Annie Ernaux. About her father. About home. Where language is the place. And Sayat Nova was multilingual. Also in Parajanov. Multilingual and in the right place. Multi-place. Is it possible to remove a language from a place? Yes, it’s possible! They tear it and throw it out. They uproot it. When the speakers are removed. And then that other, intelligible but no longer understood, that out-of-place language reports every day: “Russian peacekeeping contingent continues to carry out tasks in the territory of Nagorno Karabakh. No ceasefire violations were recorded.” Russian peacekeeping contingent continues carrying out tasks in an out-of-place language in a place where there are no locals any more. There are no people whose peace the Russian peacekeeping contingent was given the right to protect through acting in its language.

You will be misunderstood. They did not say it, when you published the text about your Azerbaijani classmate in the pre-forty-four-day-war place. But in the post-forty-four-day-war place they started to say it. Even though it seemed you spoke the same language. You and the ones saying it. The tongue gives your name. You turn back. It is your older colleague. “How are you?” he asks. “How should I be? Like everybody else.” A usual exchange of words. “Yes, and I have finally created that little cloud today,” says your Armenian colleague. You don’t get it at the beginning. But then the language does its thing: your colleague likes to translate everything. He means the iCloud. “Yes,” your colleague continues, “I’ve created it and uploaded all my documents. Who knows, what would come next, you should be ready, so when needed your documents are with you.” Your colleague does not come from that place. His grandfathers come from that place: from Shushi, in 1920. And he knows what is important. In life. Especially when there is a need to flee. Perhaps his homeland is the cloud he constituted somewhere in the endless and borderless virtual world. His place. No, back then you should not have written this about your Azeri classmate displaced from Aghdam. Especially since what you wrote was not about him. You made it up to understand displacement. To understand the other’s pain. Memory. Does it exist? If yes, how, and particularly where does it live?

You say good-bye to your colleague at the Charent memorial. You turn left, towards Alex Manoogian. Alex Manoogian was from Detroit. From a place, where there is a statue of Komitas sculpted by Chakmakchian. A black one. They say that the African Americans of Detroit consider him a hero of their liberation movement. Although it is clearly written on the pedestal that the Detroit Armenians dedicate the monument to the memory of 1,500,000 Armenian martyrs massacred during the 1915 Genocide. Memory is such a thing: if the one to whom it belongs to is no more and cannot share it, then it acquires different meanings, it transforms. Alex Manoogian himself ended up in Detroit as a result of the Genocide. Here he invented the washerless ball valve faucet - the delta faucet, and since inventions are protected in America, he patented it and became a millionaire. And now, in millions of corners of the world, thousands of people turn on the faucet, wash away their sleep, wash their faces and brush their teeth, tell their night dreams to the water for it to take them away, so they forget, and they don't even remember or know about Alex Manoogian. About the Genocide which resulted in Alex Manoogian appearing in Detroit, inventing his faucet and becoming a millionaire. What if there were plaques next to delta faucets in all public places in the world with the story of the inventor on them? In the language that the world speaks. Would the Genocide then become the world’s memory or would it be told to the water to take it?

Komitas statue in Detroit© Lusine Kharatyan

Komitas statue in Detroit© Lusine KharatyanAlex Manoogian is lying under your feet. Nemesis is on the left. A monument erected after the forty-four-day-war. The newest memory stuck in the skin of Yerevan. In the Ring Park. An intersection down from the poet of freedom Nalbandyan, who is exposed to the wind in front of the National Security Service building, and the monuments praising Armenian-Russian friendship and remembering Yezidi and Assyrian genocides. Yes, the enlightened and enlightener Nalbandyan, who was thrown into the prison by the Tsarist Okhranka proudly stands in front of the KGB building, and that building grows from inside his body on Nalbandyan street. Yes, it is not only your very own Genocide that you remember, but also the ones committed upon Yezidis and Assyrians. And you are trying to forget your frenemy, which has don’t-know-how-many talentless monuments dedicated to the century-long friendship and is fully immersed in the blood-kneaded body of the city.

Yezidi Genocide monument

Yezidi Genocide monument Assyrian Genocide monument© Lusine Kharatyan

Assyrian Genocide monument© Lusine KharatyanThey had applied to the Yerevan municipality for getting the permission to erect the Nemesis monument before the war. The city council was wondering if it made sense to erect yet another monument in a place where there were so many monuments narrating the Genocide, and there were also monuments dedicated to the Armenian avengers of different years. But the forty-four-day happened and there were no more multiple histories, there was history. The monument was erected, Turkey was “hurt” and stopped the flights to Yerevan, once more changed its language of communication with Armenia. What a disrespect towards Turkey, “how dare you commemorate the terrorists.” You offend the Turkishness. Kemal would say. So, you desire revenge. Nikol tried to explain that “One of the shortcomings of democracy is that the authorities or the head of the government is not everything and does not control everyone. If you want to know my opinion, I think it was the wrong decision, and that the implementation of the decision was also wrong.” But now the monument exists. Between the Charents Memorial and Nalbandyan’s statue.

Nemesis monument© Lusine Kharatyan

Nemesis monument© Lusine KharatyanAnd although Tehliryan assassinated Talaat in Berlin, and then there was a trial where he was found not guilty by a Jury of 12, a trial influenced Lemkin in coining the definition of genocide ... almost nobody remembers about it today. Because histories are always buried under the history. And that history is told in the language of the powerful. From the position of The History. And that language imposes its rules.

In Armenian, the language of memory and memorialization is imposed by the memory of genocide. It is the one and only way of narrating that buries all the other histories, which do not have a language of their own. The alternative was the all-Soviet language for telling the history. Stepanakert’s Bratsky Magila [2] was an interesting place to remember and memorialize the death. It started with a classic monument dedicated to the Patriotic War, then it grew and expanded with the gravestones of the participants of the Karabakh wars, further branching to the victims of Sumgait pogroms, and Genocide memorial. “To the victims of the Great Armenian Earthquake” was written on the monument dedicated to the victims of the 1988 earthquake. When the only language to narrate disaster is the language of the Great Armenian Yeghern [3], an earthquake also becomes national. Earthquake is nationalized as well.

l

Earthquake monument© Lusine Kharatyan

Earthquake monument© Lusine KharatyanNo. Your ear does not like that “GREAT” word. Were you languageless, so that the language of the power became the language to narrate the Genocide? You, who speaks one of the oldest languages of the world and have continuted to write in that language since the fifth century? Is it that the Soviet-Armenian language of genocide took its structure from the Soviet “Great October Revolution,” or “Great Patriotic War” or “Great Victory”? Or maybe the Great Purge? Did this linguistic structure exist in Western Armenian? The language of power is overbearing. Get rid of the language of power. For multiple histories to exist. For multiple memories to exist.

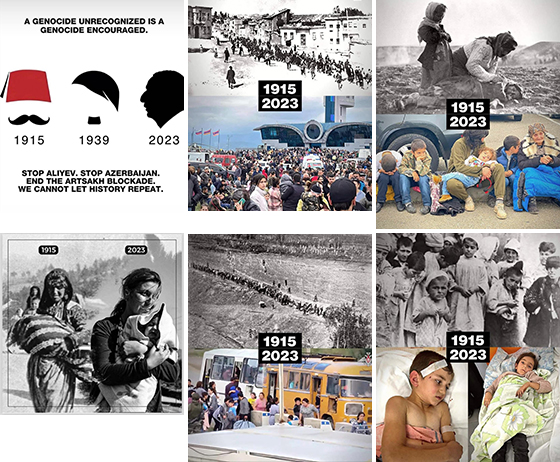

The Azerbaijani attack following the nine-month siege of Artsakh/Karabakh once more buried the histories. Or the possibility of histories. Buried them deep, very deep. Or displaced them. There is neither place nor time to create a new language for narrating the disaster. Especially since the language and the history are deeply ingrained in the mind of the people. And in addition to public memory, there is also personal and family memory. Personal and family histories stretching from Artsakh to Armenia are told in the public, intelligible, comprehensible, cliché and mainstream language and forms of the Genocide narration.

Iconography of the 2023 displacement of Artsakh Armenians© Collected from social media posts by Lusine Kharatyan

Iconography of the 2023 displacement of Artsakh Armenians© Collected from social media posts by Lusine KharatyanAnd you want the language of the delta faucet to be the language of the world. Wasn’t it invented so that the hands are not exposed to bacteria after washing them? So that you do not close the faucet with the hand, but push it down. This is the narrative you have chosen. This is the story of antibiotics and not the story of the atomic bomb. And you want Alex Manoogian’s story to be posted next to delta faucets in all public spaces of the world: hotels, theatres, concert halls, sports complexes, universities and schools. And it would be written:

The Delta Faucet: invented by Alex Manoogian, who survived the 1915 Armenian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire and moved to the USA with his family.

Can you imagine how many people will have the Armenian Genocide nailed in their memory? A worldwide monument. Exactly like Armenians. But don't you want the language of the faucet to be the language of the world? Because it is the language of antibiotics and not the language of the atomic bomb.

Somewhere in a different reality the out-of-place language reports:

Information bulletin of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation on the activities of the Russian peacekeeping contingent in the zone of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict (October 23, 2023)

The Russian peacekeeping contingent continues to carry out tasks on the territory of Karabakh. Continuous interaction with Baku aimed at preventing bloodshed, ensuring security and observing the norms of humanitarian law in relation to the peaceful population is supported.

No violations of the ceasefire regime in the zone of responsibility of the Russian peacekeeping contingent have been recorded.

And you delete your documents from iCloud. You hesitate for a moment. And then you upload the documents to the iCloud again. And the photos too. Of family, life, home, your loved ones, and the place. You are a human, you don’t know where and when you’ll end up. Maybe you'll need to buy additional memory? So that your displaced homeland might have a place to live.

[1] Quoted from Lucine Kharatyan's story #America_place Pregnant.

[2] «Братская могила», in Russian “Brotherly grave,” a place for the mass burial of people who usually died together in a battle. In Armenia it is also used with respect to WW II memorials, where the names of people are written, but the people are either missing or buried somewhere in the place where they fought.

[3] “Yeghern” is the term used by Armenians to refer to the Armenian Genocide.

Belarus

BelarusНапярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusOn the eve of the unknown the Belarusian writer is playing with the past

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusIm Angesicht der ungewissen Zukunft spielt eine belarussische Schriftstellerin mit der Vergangenheit

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusНакануне Неизвестного беларуская писательница играет с Прошлым

20 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaՌուսաստանն օգտագործել է Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի հակամարտությունը որպես իր աշխարհաքաղաքական շահերն առաջ մղելու սակարկության առարկա

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaRussia used the Karabakh conflict as a bargaining chip to advance its geopolitical interests

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaWie Russland im Spiel um seine eigenen geopolitischen Interessen den Berg-Karabach-Konflikt als Trumpf nutzte

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaКак карабахский конфликт стал разменной монетой в российских геополитических играх

12 December 2023 Georgia

Georgiaამბავი ქართული პოსტკონსტრუქტივიზმისა

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaThe history of Georgian post-constructivism

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaDie Geschichte des georgischen Postkonstruktivismus

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaИстория грузинского постконструктивизма

11 December 2023