Belarus

BelarusЖыццё пад сталом

Напярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

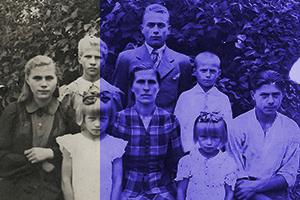

20 December 2023 Author's Belarusian family© Image from the author’s private archive

Author's Belarusian family© Image from the author’s private archive

Instead of rounding up ‘the year’s events’ (predominantly sad), we decided to publish a text by the Belarusian writer whose books, translated into many languages, tell stories about her family and her hometown in Western Belarus. Finding and preserving memories is her way to handle everyday life. In her poetic essay T.S. is playing with the past, clothing and feeding her dead.

Беларуская English Deutsch Русский

Once Mum was visited by an acquaintance of her age.

Our flat filled up to the ceiling with a complex combination of smells: catnip, fried onions,

“They’re not like us at all,” Mum was saying.

“They’re empty on the inside,” assented her acquaintance.

“They never starch or iron the laundry. I don’t get that.”

“And the arrogance! The arrogance!”

Mum’s acquaintance, in spite of her age, had a thick plait rolled on top of her head into a heavy spiral the colour of an autumn cloud. Mum’s

If there was one thing I was afraid of as a child, it was becoming a waitress.

It would be interesting to find out why. I hoped that a conversation with a waitress would help but she died suddenly. The only waitress I knew. From the town of Truskavets. I liked this word a lot, just as I liked truskawka, strawberry in Polish. The waitress had a heart attack and she was no more. All I had left were the memories: of her smell, of her hair, and another one – of the bed linen.

∗∗∗

Mum was very serious about bed linen.

Before washing, the linen was boiled for a long time in laundry soap, grated on a large grater. Swollen bubbles of white fabric were pushed back into the boiler with a wooden rolling pin. The bubbles stubbornly resisted as if they wanted to erupt out of the boiler and become free …but down came the rolling pin. After boiling, the linen was washed on a washboard. We did not have a washing machine. Then the linen was starched, rinsed and squeezed with bare hands.

Then a folding yellow wood table would be unfolded. For weeks, the folded table waited behind the bedroom door for the moment that a warm plaid was spread over it and the coarse tablecloth woven by Grandma years ago was put on top. Then Mum filled her mouth with water from a single litre enamel mug and sprayed the starched sheets through her compressed lips.

My favourite part of the process was about to begin: organising my life under the table.

It always happened when Mum ironed a white mountain of starched linen for a few days (for months, years, centuries as I thought then). Under the table, I would arrange my doll furniture. It was enough to sit all my dolls on toy chairs, to put the smallest ones in beds, to place the biggest pupsiks [∗] on stools around the kitchen table. A place of honour in the kitchen was occupied by a kredens (this is what we call, in the Polish manner, a cupboard) not painted, as was often the case with doll furniture, but with real sliding drawers, szufladkas (we always say szufladka, never ‘drawer’). There was a gas stove with metal burners. Too bad you could not light them. And there was a fridge, unpluggable. That did not worry me. Once I laid out some meals on the shelves, unfinished by the pupsiks. By the time I remembered them, the meals had turned green and dry. They had taken a new, artistically acceptable, form.

The doll furniture was made of wood.

Everything looked as if it were real. The dolls at the toy table under the folding

The ‘thick plait’ of Mum’s acquaintance from Truskavets suggested otherwise ... that her job was not that bad as long as her hair did not unravel. But then, under the table, I had no way of knowing that. I lived there in a silent

∗∗∗

There, the pupsiks always had names.

For example, they could be called Sasha, Yura, Sasha and Yura. No, no names are repeated. These are real names of my classmates. And these were four different boys. Two Sashas and two Yuras who died one after another very shortly after school was over. One Sasha was the most handsome boy in school; the other was nervous, thin, with curly hair. I learned about his untimely death 35 years after graduation when I saw his curly head on a monument in the new cemetery. One Yura did poorly in school, I liked the other. None of them lived to be thirty, each for different reasons and for one common reason – alcohol abuse.

I will treat them to thin blinis with butter and sugar.

On Sunday mornings Mum would cook a large pile of blinis, she would put a piece of butter on every blini and sprinkle it with sugar. Then she would cut the pile like a cake.

Pupsiks look the same so they can be dressed in identical school uniforms.

Only one of them, who I liked the most, had a grey suit on but in my dreams I always see him wearing a black one.

He once came to me in the evening holding a string bag full of oranges in the dusky hallway. I asked him:

“Why haven’t you come for so long? You knew I was waiting.”

“I got delayed because of business.”

I did not ask what kind of business he might have had in the afterlife. It is not polite to ask about that under the laws of sleep. It is even forbidden. I just hugged him and kissed him right on the lips. He behaved with restraint as if he came to visit me in hospital. He left after a short while. I tried not to let him go. I held his hand. The transparent hand remained in mine but he faded away.

∗∗∗

The pupsiks and the dolls can be called by the Polish family’s nicknames.

None of us knew that they were members of the Armia Krajowa underground during the Second World War. The whole family. The apartment in Białystok was a safe house. Everyone had an underground nickname. The

In order to sit the Polish relatives I have to remove from the table one pupsik, add three dollies and bring three armchairs from the

Author's Polish family© Image from the author’s private archive

Author's Polish family© Image from the author’s private archiveI had a toy sewing machine.

It sewed like a real one. Mum taught me to sew cotton sundresses and bonnets on the sewing machine. If you can sew a bonnet, making a cloak is a piece of cake. Feed the cloth into the sewing machine, sew a simple hem to seal a narrow strip on one side, thread a lace through so you can tie it at the neck. Golden, silver, bronze pieces of fabric – you have to think where to get them from. As children we would go hunt for them under the windows of the military tailor shop around the corner. One could always count on finding discarded scraps of fabric there. Amidst odds and ends, one could sometimes find pieces of natural leather. Once I even came upon a good lump of yellow leather and yellow was just as good as golden. The

For my Polish relatives, I will serve kapuśniak, thick sauerkraut soup with the obligatory addition of dried mushrooms, mainly porcini. This was Mum’s favourite dish prepared to my Polish great-aunt’s recipe. I saw my Polish great-aunt only once. She was a remarkable person. My great-aunt never took off slanted sunglasses, even indoors. She wore flared trousers while other grandmothers did not wear trousers at all. She smoked, and everyone pretended it was fine. My great-aunt was in the habit of giving to her grandchildren Polish silver groszy that looked like circles cut out of starched homespun cloth and painted with cheap silver paint (the same as the oven in the room where she was giving away the painted coins). Light, useless coins. Grandma also treated us to Bolek i Lolek chewing gum. I would take the gum to the kindergarten. Everyone asked me: “Let me have a chew from your mouth.” The entire class chewed my gum in turns. My yard friends chewed it too.

From time to time my yard friends looked under my table.

We went to visit each other through the basement passage. To every flat belonged a section of the basement where preserves, skis, sledges and potatoes were kept. The basement had an earthen floor. The light in the basement passage was broken. Running there was scary but that way was a lot shorter then through the street.

∗∗∗

Under the table, I would dress Dad’s family in white.

Because, firstly, in the 1919 photo taken in Vitsyebsk, the great-grandmother is wearing a white dress with a drawn thread work band and, secondly, Dad came to me in my dreams wearing a white suit with a matching waistcoat. Everything was white: the bow tie, the fashionable patent leather shoes. So let everyone wear white, like Dad with his grandmother, his mother’s mother. The great-grandmother’s first husband was a White Guard officer. He was executed by a firing squad during the Red Terror. His daughter, my grandmother, used her stepfather’s surname, her patronymic was not her father’s either. Her stepfather felled trees for ten years in Siberia. He had worked as an engineer at a munitions plant and was sentenced to labour camps after a blast furnace explosion.

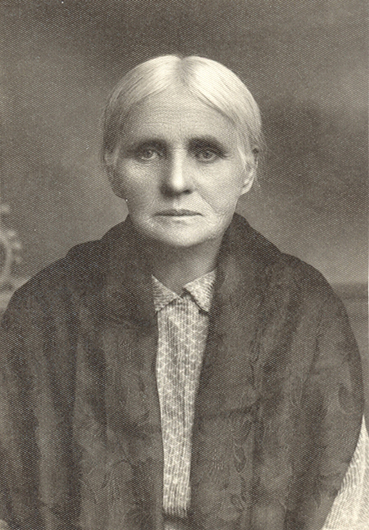

Author's father's grandmother (left)© Image from the author’s private archive

Author's father's grandmother (left)© Image from the author’s private archiveGrandma looked like the popular singer Klavdiya Shulzhenko.

As a little girl I would tell everyone that my grandmother was Klavdiya Shulzhenko. Grandpa was a chief of communications during the War. He brought his division out of encirclement, leading soldiers in hand-to-hand combat with the enemy. He was awarded the Order of the Red Banner. For re-establishing communication in difficult combat conditions he was awarded the Order of the Red Star. When I was little I did not know any of that. Grandpa smoked a pipe. I liked the smell of tobacco in all corners of the tiny khrushchevka flat on the outskirts of Riga. During Grandpa’s funeral, soldiers were carrying many awards on red cushions in front of the coffin. At eight I was not interested. After Grandpa was buried the soldiers fired volleys over the grave. He and my Riga grandmother had three sons. So I will sit two dolls – my grandmother and great-grandmother – and six pupsiks – my great-grandfather the officer, my great-grandfather the engineer stepfather and my grandfather the communications officer with his sons.

Author's Latvian family© Image from the author’s private archive

Author's Latvian family© Image from the author’s private archiveI will feed them Riga sandwiches.

It is the best supper, quick and simple. Butter goes on top of a slice of rye bread, salted sprats on top of the butter, hard-boiled egg sliced in circles on top of the sprats, onion rings on top of the egg.

I would call them all by one name: Mądrostki.

This name refers to a coat of arms. Our great-grandmother was a noblewoman. Grandpa had been serving in the army since 1929. When it became known to military headquarters that his wife, now pregnant, was concealing her real family name, they tried to make Grandpa divorce and leave her: “Otherwise, the outcome may be most unpredictable.” Grandpa was saved by the War. He became a hero. His obstinacy was forgiven.

∗∗∗

Mum’s family is the most numerous.

Seven children. Mum, Dad – locally pronounced as mamusia and tatus’. The parents of Mum’s tatus’, my great-grandmother and great-grandfather, lived with them. And so did Dad’s sister. All of them were crammed into

Grandpa’s sister after her first failed marriage lived with her brother’s family for a long time.

A few days after the wedding – she was married to a neighbour many years older than her – she came home. Never told anyone what happened. During the first days of the war her ex-husband was killed. That was the only fatality in the entire village. She said then: “The asshole is dead at last.”

All of them were simple peasants.

They worked without looking up from dawn until the first evening star was seen in the sky. Then came the Soviets who forced the family to give up their only horse to the collective farm, the kolkhoz. Grandpa took the horse himself to the communal stable. Back at home, he sat down and began to cry. He could have drunk to feel better but Grandpa did not take alcohol. I remember the famous letter to the American President from a chief of a Native American tribe that was being moved to a reservation. Grandpa would have said the same words: “And what is it to say goodbye to the swift pony and the hunt? The end of living and the beginning of survival.”

They dismantled the threshing barn.

Its debris was left to rot in the burdocks behind the village by order of the kolkhoz bosses. Grandpa built the barn before the war. He was helped by a friend from a village across the river. I learned this accidentally from Mum when a village tailor charged very little for making my winter coat warmer to wear. I bragged about it to Mum. She asked me: “Who did it for you?” – “You wouldn’t know.” – “Tell me anyway.” I told her. “Well, her grandfather together with our tatus’ put up the threshing barn some time before the war. It was a good barn, bright and spacious.” That is how I once again became convinced that Mum knew everything about everyone. To that barn during the war Grandpa brought from town a little daughter of his rich Jewish friend. Village kids – barefoot, tanned to blackness, covered with boils and scabs – played with the

Before the war, my great-grandmother and great-grandfather had their pictures taken in a Jewish photo studio.

Author's great-grandmother© Image from the author’s private archive

Author's great-grandmother© Image from the author’s private archive Author's great-grandfather© Image from the author’s private archive

Author's great-grandfather© Image from the author’s private archiveIn 1933. These are the only photos of them. Two small portraits on

My great-grandfather has a smooth forehead, unlike his wife. His grey hair is darker. My great-grandmother has an impeccable parting in her white hair, her lips are thin. My great-grandfather’s lips are thick. The lower lip to be precise. Over the upper lip there is a bushy moustache with the tips curved upwards. A dandy. My great-grandfather is smiling slightly. Only now, looking at the photo I see that my great-grandfather looks like Burt Lancaster, the American film star who always smiled a hundred-teeth smile. My great-grandfather’s teeth are not seen, but one would want to assume that the two men had the same quality teeth. Mum, for example, had perfect teeth until the end of her lifetime. My great-grandmother was the spitting image of Blessed Mother Teresa. She also had a mournful, downturned mouth.

Grandma and Grandpa also had their picture taken together only once.

This is not a set of two portraits as in the case of my great-grandmother and great-grandfather. Very young, well-dressed Grandma and Grandpa are standing side by side in a beet patch against the background of young lilac bushes. A dark dress, a dark suit. Their hands are hanging down like someone else’s, like working tools. Their hands were in fact working tools. Both are looking into the lens with well-concealed fatigue, with

Author's grandmother and grandfather© Image from the author’s private archive

Author's grandmother and grandfather© Image from the author’s private archiveThere is a post-war photo taken in the same spot.

It’s a photo of Grandma with all her children posing against the same lilac bushes in blossom. Not quite the same though: the lilac bushes grew denser. The look is the same on Grandma’s face. She will keep it until her death. The girls are wearing light-coloured dresses, the boys are wearing white shirts. Grandma has a checkered suit on. I would dress seven dolls and five pupsiks in Belarusian folk clothes. Which they never wore. And I regret they did not.

There was one name for all of them: Polinary. After great-grandfather Apollinary. Even I was once called Polinarova in a shop: “Are you not Varya Polinarova’s daughter? You look just like her.” It took me a while to get what it was about.

I will serve them a potato kishka. This is a special, rare dish: you grate potatoes on a fine grater, add pork scratchings with onion, stuff everything into a pork gut and leave it in the oven for an hour. These guests of yours will have to wait a little longer than the other ones, but for a good reason.

∗∗∗

Now Mum is done ironing.

The table is back in place, behind the bedroom door. The dollies and pupsiks are squinting at the brightness. Their eyes have not been weaned to accept the daylight. They spent so much time under the table that they nearly turned blind.

Translated from Russian by Alexander Stoliarchuk

[∗] Pupsik was a

Belarus

BelarusНапярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusIm Angesicht der ungewissen Zukunft spielt eine belarussische Schriftstellerin mit der Vergangenheit

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusНакануне Неизвестного беларуская писательница играет с Прошлым

20 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaՌուսաստանն օգտագործել է Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի հակամարտությունը որպես իր աշխարհաքաղաքական շահերն առաջ մղելու սակարկության առարկա

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaRussia used the Karabakh conflict as a bargaining chip to advance its geopolitical interests

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaWie Russland im Spiel um seine eigenen geopolitischen Interessen den Berg-Karabach-Konflikt als Trumpf nutzte

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaКак карабахский конфликт стал разменной монетой в российских геополитических играх

12 December 2023 Georgia

Georgiaამბავი ქართული პოსტკონსტრუქტივიზმისა

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaThe history of Georgian post-constructivism

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaDie Geschichte des georgischen Postkonstruktivismus

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaИстория грузинского постконструктивизма

11 December 2023 Moldova

MoldovaCe se întâmplă cu Biserica Ortodoxă din Moldova

4 December 2023