Belarus

BelarusLife Under the Table

On the eve of the unknown the Belarusian writer is playing with the past

20 December 2023 © Har Toum

© Har Toum

In September 2023, following the military aggression of Azerbaijan against the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh, more than one hundred thousand people were forced to leave their homes and seek urgent evacuation from Stepanakert to Armenia. For many Armenians from Karabakh, this was not their first experience as refugees. The pogroms in Sumgait and Baku, the war in the early 1990s, the ‘44-day war’ of 2020 and the ethnic cleansings of 2023 – all ongoing for more than thirty years – have compelled hundreds of thousands of Armenians to seek refuge and a new home in various countries. Cultural anthropologist Eviya Hovhannisyan shares the stories of people who have endured multiple displacements. Based on her fieldwork, she depicts their traumatic journeys and the challenges they encounter in the process of repeated migration, attempting to escape from multiple wars throughout their lives. [∗]

Հայերեն English Deutsch Русский

In the town of Goris, a middle-aged man noticed my overalls and struck up a conversation. It turns out, on September 28, 2023, he was compelled to move from Karabakh to Armenia because of Azerbaijan's military escalation, which led to a mass exodus of the Armenian population.

“Are you from Armenia? Do you know where the town of Chambarak is? The lady from the registration service said it’s not far from Yerevan, just a forty-minute drive from the city. They’ve offered me and my family a house there but we’re not sure if we should go. We’ve already moved three times. First in 1990 from the village of Zurnabad, in the Khanlar region, to Hadrut. Then in 2020 from Hadrut to Stepanakert. Now, we’re a bit lost on where to go next.”

”No, they are wrong. Chambarak is located past Sevan, heading towards Ijevan, not far from the Armenian-Azerbaijani border. It’s approximately a two and a

In those days, social networks were buzzing with messages that some of the forcibly displaced persons from Artsakh would be resettled in the border villages of the Tavush province of Armenia: Chinar, Chinchin, Berd. Inside, I was filled with outrage, cursing under my breath – these people should not be thrown from the frying pan into the fire. Part of the arable land in the village of Chinchin is inaccessible to the local population as the territory is under the direct supervision of Azerbaijani border guards. Here and there in the village, signboards warn of possible shelling. In other words, forcibly resettled Karabakh families are being directed to a place where the daily fear of a possible escalation of the war persists.

Then two stories came to my mind that I had written down in Kharkov in 2019: they evoke forced multiple relocations of families escaping endless conflicts, each time abandoning a built house, leaving behind work, social connections and memories ...

∗ ∗ ∗

The end of the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s were marked by the military conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, accompanied by massive forced population movements. The collapse of the USSR brought about various conflicts, including territorial and interethnic ones, which often involved armed confrontation. The territorial dispute between neighbors over the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region, which was part of Azerbaijan but predominantly populated by Armenians, had been smoldering since Soviet times and escalated into a war between the now-independent states. [1] As a result of the conflict's escalation on both sides, approximately a million people were forced to migrate from Azerbaijan to Armenia and vice versa.

In the early 1990s, Armenia faced a challenging economic situation as a result of the devastating Spitak earthquake in the north of the country that occurred on December 7, 1988. The situation was further exacerbated by the collapse of the Soviet Union, followed by the war and economic blockade of the country. Armenians from Azerbaijan sought to migrate to areas where there was at least some opportunity of finding work and housing.

The relocation of refugees was both planned – when organized by entire settlements – and spontaneous, with individual families moving independently. In most cases, Armenians from Azerbaijan moved on their own, without the participation or assistance of the state. As the conflict between the states evidently escalated, people started searching for houses, apartments, villages, that could be exchanged with Azerbaijanis from Armenia. Gradually, this phenomenon became widespread: Armenians and Azerbaijanis regularly exchanged houses, signed informal agreements, and executed documents on the exchange of property, as well as selling and buying new houses. [2] This undoubtedly facilitated the relocation process, since many families knew in advance where they would be moving. They could agree to, or refuse to accept, the offered exchange options or explore other, more profitable alternatives. [3] Often, entire families visited their future homes to inspect the area, meet village residents, learn about their way of life and employment opportunities, and evaluate the approximate equivalence of the real estate being exchanged.

The resettlement process was gradual and proceeded through several steps. Representatives of both sides came and went for almost three years

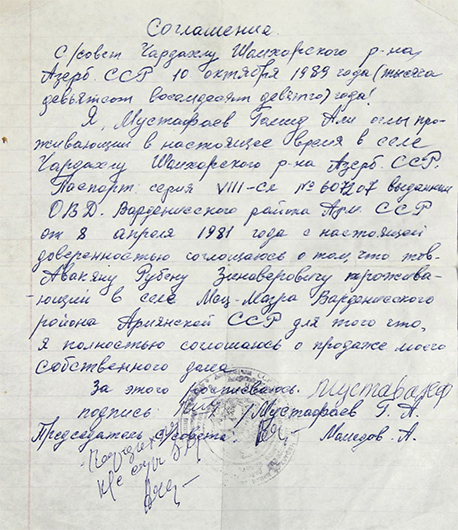

House sale agreement, Chardakhlu/Chardakhli/Chardagly village, 1989© Photo by Argam Yeranosyan

House sale agreement, Chardakhlu/Chardakhli/Chardagly village, 1989© Photo by Argam YeranosyanAs a result, some Armenians from Azerbaijan were able to exchange housing with Azerbaijanis from Armenia. Another group managed to sell their property in Azerbaijan and use the proceeds to buy a new house in Armenia. Still others, having lost everything, moved to Armenia, hoping for help from relatives and the then Soviet state; while another category left Azerbaijan for other countries – Ukraine, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan. The move to other Soviet/post-Soviet republics was influenced by various socio-cultural factors, such as environment, density of Armenian communities, and wider employment opportunities.

The forced migration of the Armenian population from Azerbaijan in the late Soviet and early

Alla (all names in the text have been changed), originally from Azerbaijan:

“We were forced to leave Baku when the situation began to escalate. First, we went to Volgodonsk, since my husband’s brother lived there. But we didn’t stay there for long. A year later, we landed in Armenia. I didn’t like Volgodonsk, it was a completely new place, a city for youthful people. People came there from all over the Soviet Union, as it was a kind of Komsomol construction project – such a hodgepodge of different nationalities and cultures. We began to worry about the future of our daughters, who were still schoolgirls at the time. After all, in Russia, especially in cities like this, morals are different, and the crime rate is high. We started to look for options on how to leave that place. Eventually, we found a Russian family from Armenia – a military family – and they agreed to swap apartments with us. They wanted to move closer to their children in Russia. So we shifted to Yerevan.” [4]

As Alla’s example demonstrates, people moved not only for economic and housing reasons, but primarily for the safety of their families. This was especially evident in conversations with refugees who were forced to leave Baku: many of them believed that living in multinational cities was dangerous. In the early

Following this logic, Alla’s family relocated from Volgodonsk to Yerevan:

“The children integrated into Armenian society very quickly and learned the language rapidly, as in Baku we spoke Russian. My youngest daughter picked up Armenian before anyone else. She was four or five years old at the time. The rest of the children learned it at school. It was more challenging for me and my husband, but somehow we managed. A year later, the children were already fluent in Armenian. I got a job at a bank, started learning Armenian letters, and even mastered typing. It was 1992.”

In the early 1990s, the economic situation in Armenia continued to deteriorate. Relations between the local Armenian population and refugees from Azerbaijan eventually began to heat up. Many refugee families, who settled in former Azerbaijani houses and villages in Armenia, found it challenging to adapt to new living conditions due to economic and socio-cultural reasons. In the initial years of resettlement, numerous families left Armenia, selling their apartments, houses and land plots to local Armenians at meager prices. These were primarily Russian-speaking urban residents from Azerbaijan who did not speak any Armenian and lacked knowledge and necessary skills in the field of agriculture. Before their resettlement, many of these refugees had been employed in various industries in the large cities of Azerbaijan.

Former Azerbaijani houses in the village of Mets Masrik, Gegharkunik province of Armenia© Image courtesy of the author

Former Azerbaijani houses in the village of Mets Masrik, Gegharkunik province of Armenia© Image courtesy of the authorIn the initial years of resettlement, linguistic and professional factors were the primary contributors to the alienation of refugees. The languages most refugees spoke included Russian (as urban residents in Azerbaijan attended Russian-language schools), Azerbaijani, and a local dialect of the Armenian language which significantly differed from literary Armenian.

Alla continued her story:

“In Armenia we were labeled ‘inverted Armenians’ [shurtævats], because we didn’t speak Armenian and grew up in an Azerbaijani environment. About twenty years ago, it was very difficult in Yerevan; they didn’t like Azerbaijani-Armenians. When I spoke Russian, they wouldn’t even answer me; they would say, “You’re Armenian, why don’t you speak Armenian?”

It is for the reasons mentioned above that many refugee families shifted from Armenia to other countries.

Alla has three children – two daughters and a son – all living in Kharkov now:

“We left Armenia for good in 1994. Initially, we held onto the apartment for a while thinking maybe we would come back. I left the keys with my brother so that he could occasionally check on the apartment. But after six years, when it became clear that we wouldn’t come back, we decided to sell the apartment to buy a new one here. By that time, my children had already graduated from high school and college, got jobs, and my eldest daughter got married ... If my children had been willing to return, I would have headed back. But they didn’t want to go back.”

For various reasons, refugees tried to retain their homes in Armenia. Firstly, owning a home in Armenia, they could potentially return to their ethnic homeland [5] at some point. Secondly, this served as a cautious strategy in case of possible new forced displacements. Thirdly, refugees sometimes did not want to sell their property because they did not have alternative holdings in their new resettlement locations. After moving to Kharkov, Alla’s family initially lived in the house of her brother-in-law, then rented an apartment for some time. Then Alla sold their apartment in Yerevan and the family received the opportunity to buy a plot of land in Kharkov. On this site they built a private house where Alla lived with her husband and two children until the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine began in 2022.

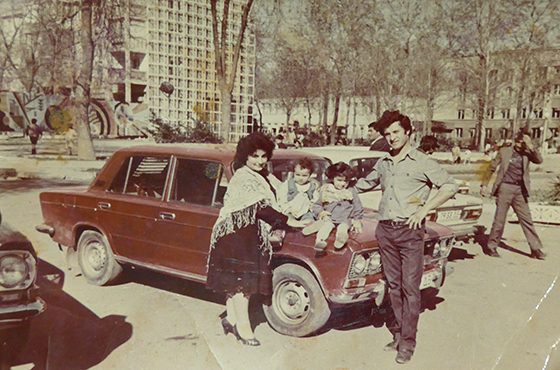

Alexey and his family in Dushanbe, late 1980s© Photo from the family’s private archive

Alexey and his family in Dushanbe, late 1980s© Photo from the family’s private archiveAs illustrated by these stories, refugees repeatedly changed their places of residence and chose new destinations for resettlement, guided by various considerations. Most often, these decisions were influenced by family ties. Some were oriented towards Russian-speaking or majority Armenian environments, while others were motivated by economic considerations and employment opportunities. Numerous examples abound where people, concerned for their safety and the

Alexey from Shamkhor in an interview. [6]

“During the pogroms in Azerbaijan, we exchanged our house in Shamkhor for a house in the village of Shishkaya [author’s note – now the village of Geghamasar, Armenia], but we didn’t end up settling there. Instead, almost right away, we moved to Uzbekistan where my brother worked. Back in the Soviet time I had often traveled to Tashkent for contract jobs, so we decided to stay there temporarily. From Tashkent my family and I moved to Dushanbe, where they offered me another job. But in the early 90s it became very difficult to live there, especially for the Russian-speaking population so we decided to move back to Armenia, then to Krasnodar and finally, by car, to Kramatorsk.”

The example of this family is indicative in that it quite emblematically illustrates the possible ways of multiple resettlements of a family of Armenian refugees coming from the Azerbaijan SSR. Alexey’s family moved from the city of Shamkhor to the village of Shishkaya, since in November 1988 they successfully exchanged houses with an Azerbaijani family from Armenia. However, just a few months after the resettlement, they left for Central Asia (first Tashkent, then Dushanbe), where Alexey managed to find a job.

The car in which Alexey moved from Armenia to Kramatorsk in 1997. Photo taken in 2019© Image courtesy of the author

The car in which Alexey moved from Armenia to Kramatorsk in 1997. Photo taken in 2019© Image courtesy of the authorIn the early 1990s, Alexei and his family returned from Central Asia to the village of Shishkaya, where their home remained. Here they began engaging in small trade and car repairs. But the Armenian environment turned out to be extremely challenging. By the second half of the 1990s, Alexey and his family moved from Armenia to Krasnodar on a cargo plane:

“I drove that car straight onto the cargo plane and that’s how my family and I left Armenia. We were dropped off in Krasnodar, from where we drove wherever the road took us. We drove the car to Kramatorsk where it broke down and we stayed here. We’ve been living here for 25 years now.”

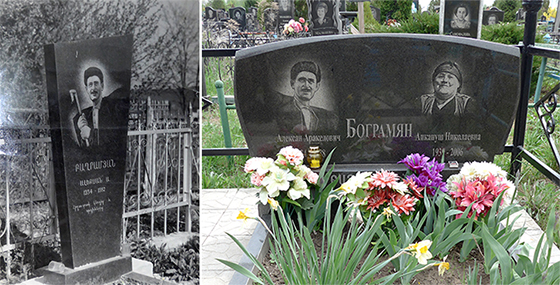

On the left is the grave of Alexei’s father in Azerbaijan, on the right is a memorial stone over the grave of his mother in Kramatorsk with a picture of his father from the old grave. Photo taken in 2019© Image courtesy of the author

On the left is the grave of Alexei’s father in Azerbaijan, on the right is a memorial stone over the grave of his mother in Kramatorsk with a picture of his father from the old grave. Photo taken in 2019© Image courtesy of the authorIt took fifteen years for Alexey, his wife and his son to build a house in Kramatorsk. Some time after the family settled there, his mother moved in with Alexey. After her death, he erected a monument over her grave with the picture of the grave of his father who is buried in Azerbaijan. This practice of ‘moving’ graves is very common among Armenian refugees. Often, on the tombstones of forcibly displaced Armenians, one can find photographs and names of people who died before the start of the conflict.

Various vectors of Armenians’ relocation from Azerbaijan can be tracked. The choice of each subsequent destination was determined by certain factors. At the beginning, some were able to trade their houses in Azerbaijan for houses in the former Azerbaijani-populated villages of Armenia, while others moved to Central Asia where there was at least some income in the first

Repeated relocations brought about certain changes in the migrants’ lifestyle and shaped their attitude towards migration and, in particular, towards subsequent relocations.

Alexey concluded his story:

“We fled from Shamkhor to Tashkent and then to the village of Shishkaya where we were able to exchange our Shamkhor house. But we couldn’t stay in the village. Our children attended a Russian school and kindergarten in Azerbaijan and took music lessons. But we couldn’t adjust to the village. One might say we moved to Kramatorsk quite spontaneously. It was a fight for survival.

Since 1988, Alexey and his family have moved from one place to another and have eventually ended up in Kramatorsk. Throughout a series of relocations, he has resorted to various survival practices in the challenging situations caused by the living conditions in each subsequent place of relocation.

∗ ∗ ∗

The Second Karabakh War of 2020 and the subsequent forced mass exodus of the Armenian population from Karabakh in September 2023 created a situation where displaced families found themselves at the beginning of a long refugee journey. Unlike the first phase of the Karabakh conflict, after the 2020 war and the spontaneous deportation of the population, new refugees were not given the opportunity to pack their belongings, exchange or sell property, make decisions and discuss the destination of possible resettlement. The situation turned out to be even more disastrous. For the last year, since December 2022, Karabakh has been under a de-facto blockade and, by the time the forced exodus began, the local population has not only lacked basic food products and necessities but also fuel for cars to simply leave.

[∗] This article is the result of the author’s research project undertaken in 2019. The research was carried out within the framework of the CISR e.V. Berlin project "Memory Guides: Sources of Information for a Peaceful Conflict Transformation."

Translated from Russian by Kun

[1] Gamagelyan, F., Rumyantsev, S. (2013) Armenia and Azerbaijan: “The Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh and a New Interpretation of Narratives in History Textbooks.” // Karpenko, O.,

[2] Huseynova, S., Akopyan, A., Rumyantsev, S.,

[3] Hovhannisyan, E. On Exchange of Houses and Multiple Migration. ZINEadadar #3, Restless suitcase. CSN Lab, Yerevan, 2023,

[4] Alla is a 62 year-old refugee from Baku. Interview: Kharkov, April 2019.

[5] The term ‘ethnic homeland’ is used here intentionally, because in the case of Azerbaijani Armenians, in a narrower sense, their minor homeland/place of birth is considered to be Azerbaijan, while their ‘ethnic homeland’ is Armenia.

[6] Alexey is a 70 year-old refugee from Shamkhor (now the city of Shamkir in Azerbaijan). Interview: Kramatorsk, April 2019.

Belarus

BelarusOn the eve of the unknown the Belarusian writer is playing with the past

20 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaRussia used the Karabakh conflict as a bargaining chip to advance its geopolitical interests

12 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaThe history of Georgian post-constructivism

11 December 2023 Moldova

MoldovaWhat is going on with the Moldovan Orthodox Church

4 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaGeorgian “political Orthodoxy” and Russia

28 November 2023 Belarus

BelarusCan Belarusians critisise Western policies?

22 November 2023 Moldova

MoldovaAbout the underestimated danger of division into “us” and “them”

20 November 2023 Armenia

Armeniaand you said: there is no history, there are histories

6 November 2023 Georgia

Georgia‘Majoritarianism’ and ‘juridification’ in the service of clan governance

31 October 2023 Belarus

BelarusProminent political prisoners in Belarus have been completely cut off from any contact with the outside world for over six months

26 October 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaThe History of Cooperation and Resistance

20 October 2023 Moldova

MoldovaIs it possible to stop the rapid decline in the Moldovan population?

19 October 2023