Belarus

BelarusЖыццё пад сталом

Напярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 Vitali Tsyhankou at the march to celebrate Belarus Independence Day (Dzen’ Voli – Freedom Day). Warsaw, March 25, 2023

Vitali Tsyhankou at the march to celebrate Belarus Independence Day (Dzen’ Voli – Freedom Day). Warsaw, March 25, 2023

After the 2022 protests and the repression that followed, hundreds of thousands of Belarusians fled abroad. Many of them faced punishment solely for the exercise of the right to freedom of speech. But can they exercise this right now that they reside in safe countries? Sometimes, after escaping persecution, some of them speak out about the problems of the country they fled to and hear in reply: “Why, then, do you live here? Go back to Belarus.”

The author of this article is Vitali Tsyhankou, Belarusian publicist, Radio Svaboda journalist and host of his own programme on Belsat TV.

Беларуская English Deutsch Русский

I nearly made a strategic error recently. In a conversation with the landlady of my Warsaw flat I began to tell her enthusiastically how nice it was to live in Poland (of course, if you forget about the tragic circumstances that brought me there). I was saying something like:

“On the city’s outskirts there are many shops and restaurants, a swimming pool, a park, a children’s area, sports grounds, a lot of different trees, everything is nice and clean. When you walk through the Warsaw city centre all the lights are on, clubs and restaurants are full of people, you can see so many new modern buildings, museums and monuments.”

No sooner had I finished praising Warsaw than I felt I was addressing the wrong audience.

Regina replied excitedly:

“Life has become awfully expensive, eggs have gone up in price, butter has gone up in price, the public transport is poor, the banks are raising interest rates and [Poland’s ruling

Having heard her highly critical assessments, I thought that now my kind and friendly landlady was probably about to raise the rent or even kick me out of the flat. Having heard her highly critical assessments, I started to look around cautiously to see if a Russian or Belorussian TV crew was hiding somewhere in the bushes ready to air a story with the tagline: ‘A retired Polish lady explained to a fugitive journalist how hard it is to live in Warsaw.’

This is a joke of course. But Belarusians (both in Belarus and abroad) who criticise certain aspects of Western life have no time for jokes when they are blamed for ‘disseminating Russian propaganda narratives.’

“You work for Russian propaganda” is not the worst thing to be accused of in a social media discussion about the life in the West. Things may get worse when someone speaking about the problems of the country where they currently live is dismissed with the retort, “Why then do you live there? Go back to Belarus.” And this is often addressed to those who are known to be unable to return because they would be immediately arrested. Do people not realise how it sounds? It sounds offensive, Soviet style and very totalitarian.

Such remarks reveal the good old slave psychology: “Don’t be sassy, shut up and admire your new master.”

When Poles in their thousands join rallies against the Polish government, when they harshly criticise the state of democracy and the state-run media in their country, they are the least concerned about what Russian propaganda has to say on these matters.

When the French yellow vests went to protests and clashed with the police, they were the least concerned about how their actions would be shown on state TV channels in Belarus.

When Americans take and post on X (Twitter) horrific pictures of streets in Los Angeles and Philadelphia full of drug addicts, reminiscent of zombie apocalyptic films, they don’t care that tomorrow these pictures may be used by Belarusian propaganda.

And when Ukrainian journalists expose the corruption and the mess in their country country that is, at the same time, fighting the invaders, they help Ukraine win rather than feed material to Solovyov’s TV show [

My friend, a Belarusian who has been in Warsaw for ten years, once complained to me about his living conditions in Poland, about the inflation, about the sharp increase in mortgage rates, about those same ‘eggs and butter.’ And I said to him:

“Listen, in Belarus most of the food costs the same, if not more. Clothes in Poland are cheaper and the choice is better. At the same time, the average salary in Poland is three times as high as in Belarus. You mustn’t complain.”

He replied bluntly:

“Why should I compare Poland to Belarus? Why not to Somalia? Or to North Korea? Should I be happy that I’m not starving? That OMON [Belarusian riot police] isn’t going to break into my apartment?”

That is logic. You quickly get used to the good things. I have seen many times in my life that a Belarusian, who went to the West and began to be paid Western wages, very soon would stop comparing them to those in Belarus. Having secured an income ten times greater than he had in his homeland (which was just the case in the 90s when the average monthly salary in Belarus was about $50), that this Belarusian considered his new Western wages to be quite ‘mediocre’ or even ‘poor’ as compared with the earnings of other people in his new country.

In principle, it is a famililar argument that can be used against Belarusians in Belarus: “You’ve got enough food, you’re home and warm whereas in Africa people are starving, in Bangladesh ten people share a twenty-square-metre room, and other people don't have access to drinking water …” There is always someone in the world who is worse off than you are. But you do not think every day about how lucky you are. You perceive your current standard of living to be the norm, you are ready to criticise it and to find flaws even in the most prosperous and successful life.

Belarusians permanently or temporarily living in the West, naturally, begin to feel the problems of the locals as their own, something that people living in Belarus may find distant, irrelevant and at times annoying.

Belarus Independence Day (Dzen’ Voli – Freedom Day). Warsaw, March 25, 2023© Image from the author’s private archive

Belarus Independence Day (Dzen’ Voli – Freedom Day). Warsaw, March 25, 2023© Image from the author’s private archiveUntil 2021, I had lived in Belarus and constantly expressed my opinion – on Radio Svaboda blogs and my Facebook page – on various ‘Western’ issues including the elections in the United States, feminism, political correctness and freedom of speech, migrants and multiculturalism. I do not feel and have never felt these problems as distant or irrelevant.

First of all, I saw that those issues resonated with my readers, the vast majority of whom resided in Belarus at the time. It must be said that politically and socially active Belarusians have a fairly broad view of the world and have never been focused exclusively on local issues.

Secondly, while living in Belarus I had long felt part of the Western civilisation, ‘their’ issues were – and remain – ‘my’ issues: they worry me, they appear to me to be really important, they require thought and reflection. I am mostly concerned with the areas of life where new and unexpected developments are taking place, where in the course of just a few years public sentiment is changing dramatically. (Our Belarusian ‘eternal’ questions form another part of the intellectual landscape. Of course, the year of 2020 brought about a lot of change and shook the society but the existential problems remained the same. Sometimes I say, with bitter irony, that there is no use writing anything new, you can simply republish your own articles from twenty years ago – about the language, about Russia or about the dictatorship.)

Every time I am asked something like, “Why are you interested in that?” I want to answer: “But actually, why am I interested in life in all its manifestations? Why am I concerned about the most important issues and paths of humanity that (at least in our time) are born and formed in the West? Why am I concerned about the issues that one way or another, sooner or later, will come to us, to Belarus?”

Recently I saw on Facebook a remark by a Belarusian to the effect that the West is no longer what it used to be, that the West is getting weaker and it is betraying its essence. You can imagine how furiously he was attacked by ‘progressive’ commentators. Their rebukes and insults were so many and so varied that I would not dare quote any of them here. But what can we expect from an ordinary social media user if even a famous politician (for example, Zianon Pazniak) criticising certain aspects of Western life is likely to face a similar outpouring of hate and insults?

Meanwhile, the ‘decline’ (imaginary or real) of the West has been the subject of books, articles, popular and scholarly essays which happen to have been published not only by the conservative media but by the mainstream liberal media as well. In contrast to certain ‘politically correct’ issues, the fate of the Western civilisation has been discussed fearlessly and thoroughly. It is remarkable that according to a number of sociological surveys, young supporters of the Democratic Party demonstrate the lowest level of patriotism in the United States.

There is another aspect of and another reason for the desire of Belarusian relocants to keep a low profile. It is the determination to become model members of the new society as soon as possible which, as considered by many, should include maximum and unconditional loyalty (even if it is not required).

It is the perpetual desire to be holier than the Pope, more Polish than the Poles, more patriotically Americans than the Americans. Joining a nationalist march on Polish Independence Day and shouting, “Poland for the Poles!” is very Belarusian.

In fact, we are not the only ones to act in that way. In the United States, the majority of immigrants are not afraid to assimilate. Italians, Irish, Germans, Swedes, Poles do not create their own political lobbies because they are not worried that much about their respective historic homelands. The most powerful lobbies are formed by such ethnic groups as Jews, Armenians and Greeks who have a cause for concern. According to this logic, Belarusians should not quickly assimilate with the locals, become like everybody else, because now (and possibly for some time to come) we will need in Western countries our own active lobby with a strong national identity.

At the same time, in their desire to please the locals many Belarusians are ready to do things that they are not asked to do. It seems the Lithuanians have never been concerned about what Vilnius is called in Belarusian. But some Belarusians are putting the cart before the horse: ‘Let us say Vilnius instead of Vilnya.” “I understand that the idea to replace Vilnya in the Belarusian language with Vilnius originated from the desire to please the Lithuanians through self-humiliation,”says [Belarusian journalist and writer] Syarhey Dubavets.

Polish Independence Day (Narodowe Święto Niepodległości). Warsaw, November 11, 2023© Gennady Veretinsky

Polish Independence Day (Narodowe Święto Niepodległości). Warsaw, November 11, 2023© Gennady VeretinskyThe West does not always change for the better, there are a lot of processes that cannot but cause a lack of understanding and rejection (this is true, in particular, of me).

There appeared a tacit tendency not to discuss certain topics. In the 90s, it would be impossible to imagine anything like that. We were led to believe at the time that any subject was fit for discussion, that only complete openness could help us resolve any problem. We sought to lead our country to the West, and we were attracted not only by material goods, we were attracted by freedom of thought and speech, by human rights and the rule of law.

I have been following the US media for the last 25 years, and I have received the impression that some of them no longer seek to inform the public as widely as possible, to offer different perspectives, to provoke debate. Instead, they simply play on the side of ‘their’ political ideology and ‘their’ political authority. There is a paradoxical connection between the new technology companies, politicians and media in their effort to control the information agenda while ignoring everything inconsistent with the preferred narrative.

As a consequence, trust in the media in the United States, according to sociology, has plummeted; in the mass consciousness, journalists have become transformed from the most respected and even heroic characters (in the 1990s) into predominantly short-sighted, cynical and negative characters.

But that is just my version and my personal observation. Other people have quite different, sometimes opposite grievances against the West. Some do not accept illegal immigration, others, on the contrary, demand more freedom of movement. Some complain about political correctness, the shrinking of freedom of speech, others claim that ‘too much has been allowed to go on for too long.’

In any case, it can be stated that the attractiveness of the West and, correspondingly, of the idea of Belarus joining the European Union is not gaining popularity: it has been supported by

And this is a problem both for us, Belarusians who want to see their country as part of

Someone may say, “What exactly can you Belarusians, people of a country under dictatorship, recommend to the Europeans and Americans?” Interestingly, this kind of attitude had to be overcome by the Eastern Europeans who got rid of the Soviet rule and were eager to integrate into the Western structures. In certain circles, there was the same tendency to treat them as representatives of societies that had nothing useful to offer to peoples of long-established democracies.

However, I am inclined to think that in this case the lack of trust (to put it mildly) is coming from Belarusians themselves. It is still the same principle of ‘Who do you think you are to have a say?’ It is still the same Soviet (and now

Sit tight, be still, be happy that you have been given shelter, be silent and thank your lucky stars for your new place of abode.

However ... maybe the West does not need our eulogies, maybe the West needs our peaceful, fresh and sometimes critical look. Maybe we Belarusians are able to see what cannot be seen by the eye of ‘locals’ (I really like this word!) who are long accustomed to their reality and take it for granted.

Because we have a unique experience (of living under dictatorship) owing to which we can feel certain things more acutely and identify the threat at a point where it cannot be identified by people who are lucky enough to know about dictatorship only from books and films.

Translated from Russian by Alexander Stoliarchuk

Belarus

BelarusНапярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusOn the eve of the unknown the Belarusian writer is playing with the past

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusIm Angesicht der ungewissen Zukunft spielt eine belarussische Schriftstellerin mit der Vergangenheit

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusНакануне Неизвестного беларуская писательница играет с Прошлым

20 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaՌուսաստանն օգտագործել է Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի հակամարտությունը որպես իր աշխարհաքաղաքական շահերն առաջ մղելու սակարկության առարկա

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaRussia used the Karabakh conflict as a bargaining chip to advance its geopolitical interests

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaWie Russland im Spiel um seine eigenen geopolitischen Interessen den Berg-Karabach-Konflikt als Trumpf nutzte

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaКак карабахский конфликт стал разменной монетой в российских геополитических играх

12 December 2023 Georgia

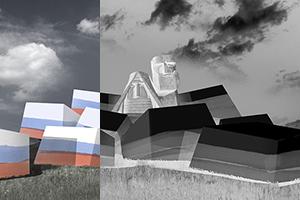

Georgiaამბავი ქართული პოსტკონსტრუქტივიზმისა

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaThe history of Georgian post-constructivism

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaDie Geschichte des georgischen Postkonstruktivismus

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaИстория грузинского постконструктивизма

11 December 2023