Belarus

BelarusЖыццё пад сталом

Напярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 © Har Toum

© Har Toum

One of the most important contemporary Armenian novels, P/F by Aram Pachyan, is scheduled to be released this autumn in German through the publishing house Kolchis. Pachyan’s prose, an amalgam of documentary and imaginative writing, delves into the themes of cultural memory, post-Soviet contexts and reinterpretation of the literary past. These themes hold great significance for today’s Armenia. Pachyan is the winner of the EUPL 2021 (European Union Prize for Literature) and one of the most widely read authors in Armenia. His works were translated into English, Greek, French and Ukrainian. In anticipation of the forthcoming German edition of the novel P/F, OSTWEST MONITORING publishes an essay by Pachyan in which the theme of cultural memory is tightly interlinked with the author’s personal experience of today’s political realities.

Հայերեն English Русский

I wrote this essay in the summer of 2023. Now it is the fall, and now the Artsakh Armenians are undergoing ethnic cleansing on the part of Azerbaijan.

To Polina Barskova

11:00 am.

A rather innocuous time.

Simplistically put, not a bad time.

A moment for coffee to cool a bit, for street vendors to holler in the courtyards of towering apartment buildings, “Brooms and fresh Sevan whitefish!”

Time for a solitary and simple breakfast, the simplest and quietest ritual in the whole wide world.

By 11:00, all sorts of spine-chilling news is already circulating online. Pardon me, human lives, but at 11:00 masses of your remains are not merely captured in photographs, they are depersonalized too. Some of you have already turned into memes while others are bouncing around like mirrored reflections in human rights offices.

The soldier who dies in the Second Artsakh War is dismembered, photographed, and the photo is sent to his mother – sent from the phone of the very same dismembered soldier. It’s 11:00. I apologize, the news was shared at 11:00, just as it was within the confines of the library.

Zaruhi recounted it.

Recounted it. Then took a trip to the bathroom, allowed her tears to flow, returned, settled back into her seat in the reading room. As timid as a first-grader, Zaruhi drew the chair closer to the desk and brushed her fingers against a slim green notebook. Her tears started anew. Her whimpering was barely audible.

When did it happen? What year? I’ve already lost track. Perhaps the fall of 2020 or 2021,

Sometime during the fall.

That much is certain.

Don’t go counting your bodies before the fall. Bodies torn apart – tissues mixed with soil, within their own separate bag. The soil is young, as are the tissues and the bag. Zaruhi dozed off there in the library. In her dream, she kept repeating thoughts about the war: “We’ve never outgrown the youth of this world.”

You can attribute everything that seems banal to a dream. Whatever you avoid, whatever fills you with terror – feel free to attribute it to a dream – make yourself believe it’ll pass, but deep down, you know it, you still won’t be able to bypass yourself.

© Image courtesy of the author

© Image courtesy of the authorIt seems like Brecht once said, I can't recall the exact wording, but something like: “The fear of appearing banal is the ultimate form of banality.” After all, Brecht had his own regrets, a twinge of remorse and guilt too. Likewise, war survivors might feel ashamed before the dead – those who survived the catastrophe find it hard to come to terms with the reality of having survived it.

Seriously. How banal can things get?

Well, let’s just roll with it.

As if he needed your say-so.

Let’s put Brecht aside for now. At the Chicago Public Library, Erwin exclaimed vehemently: “Brodsky was

All right, Erwin and his banality and his debate on poets and non-poets is all we really need here.

But you came up with an objection to Erwin: the public libraries in Yerevan initially encountered the

Looks like you are really missing the Chicago Library. You barely spent an hour there. Or to be more precise, perhaps only twenty minutes. Chances are, you won’t get back to this place where you couldn’t register a single trace of collective or personal memory loss, where no one connects their identity to another, instead of another.

In one of those Yerevan libraries a manuscript (fictional) surfaced in the reading room. Everyone knew to whom it belonged. The reader unfurled it and commenced reading out loud in the presence of their own kind: “When the heck are you going to quit poking at your memory, your Soviet past? When will you get out of the libraries and come face to face with the darn war? War is staring you right in the face. Within arm’s reach. Don't you dare lie. The war is yourself – it’s inside you. Your unfragmented body is made of war.”

I’m fed up to the back teeth with your dramatics. Hate you. I detest every single word you utter. You are all the ones who let this happen again.

When is it going to end – this windbaggery – echoing in the ears and nostrils of everyone who is still breathing, all over hell’s half acre – words – two world wars, one unsuited, the other – suited (convenient), Auschwitz, Gulag, Hiroshima, art, literature, humanite՛.

You had a knack for writing about it: largest circulation, fame, cash flow, ‘oohs’ and ‘aahs,’ accolades, discussions seasoned with a dash of rotting democracy, philippics and screams. And the most awful thing is that it was all done and is still being done with a certain brilliance.

What is more bloodcurdling than exquisite art belched out of the crematorium chimney, art whose significance is about to drive out not only the history of the crematorium’s creation and operation but also the crematorium itself? Just please refrain from this: “Through writing, we are attempting to make sense of the crematorium.”

You still don’t understand that attempts to make sense are equivalent to the crime, just as much as refusing to make sense is. Come on, go ahead, down the beaten track – keep writing and selling marvellous novels about sorrow, suffering, loss and ruins.

Wonder why you – authors and artists – are so heartless, why you keep poking fun again and again? I figured out the answer: it’s simply because you are alive and they’re not. That’s the long and short of it.

And I don't care if, from your perspective, I look like a total idiot, crazy as can be. Adorno is my guardian angel, he’s the one who lifts my spirits. My infantilism will serve as my anaesthetic shield against you. Do you still remember the motive and reason? Once again, you are alive, while they are not. Here is the banal truth for you – the dumbest one of all possible banalities. Take it, cover your vanity and hatred with it – “I” and “We.”

Here in Yerevan, people are now throwing it into each other’s faces: “You blabbering windbag, the ice cream on the Cascade stairway is weeping for you. Well, just wait and see. Soon. The enemy will reach your throat, slit it, smear the ice cream on your face, and sit on your belly to devour the rest.”

And actually, go stop the war. Me? No. You go. I have no questions for myself – you, for instance, didn’t even remember me.

For you, in the midst of you, and apart from you, I have always been and remain a nobody. You are the only ones I hold accountable. I won’t get out of my house and my library. The memory of the Soviet legacy, of the animosity and vengeance of nations will continue to be passed down through generations as if on a conveyor belt without you – without your comprehension and interpretation. There is no need for this, nor will there ever be. Remember – you engaged in this game of “making sense” in others’ stead – instead of the murderers and the murdered.

You sniff around avidly as if detecting death's scent and the moment another catastrophe strikes, there you are, the infamous distributors of death certificates. Your mercy is cynical and stinks abominably. This language of literary compassion you wield is the greatest distortion ever produced by humankind … the language of mourning, of exploiting loss. There's nothing that could shut you up. Authors, artists, intelligentsia and literati – I pass judgment on you and I condemn you. You are condemned to yourselves … so get out.

Another autumn, this time again.

Yerevan appears in a forgotten post-Soviet library.

But what if there, far away from the library realm, sorrow and joy are measured on the same scale? Yet how ironic that the measure falls short of itself, yet still they are measured. Toss in some tragedy and some comedy, the legitimate and never-exhaustible tools of aestheticizing war – who said that? – you don’t remember. Just at the entrance of the reading room. And you’re like: “not bad, not bad at all, I should remember this and slip it in somewhere.” Here, just slipped it in. Although “slip in” might not be the right expression, it’s better to say: “apply.” But is it a good idea sweetening the

Oh yes…

Zaruhi.

She is sitting motionless over her notebook in her usual manner – like a nameless Stoic philosopher, like a human being, like a scholar. She starts to write something. What, exactly, is still not clear. Zaruhi never disclosed any specifics of what she was searching for – so desperately and persistently, with the frozen countenance of a thinker determined to salvage submerged memories from the depths of library collections. Zaruhi’s fingers are beautiful, like a wondrous legend that materializes out of thin air. It’s curious how her greenish school notebook hasn’t yet run out of blank sheets, and the ink in her pen hasn’t yet dried up. As far as I remember and am mistaken, school notebooks only pack twelve sheets.

Actually, she did disclose something:

How she is studying the cultivation of wild hops in Soviet Armenia and planning to start her own hop farm. It makes me wonder – perhaps she became fascinated by the word itself? Why not? The word is the seed, and according to the

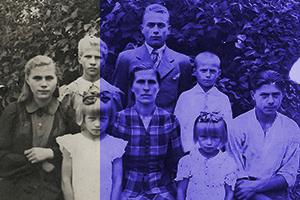

© Image courtesy of the author

© Image courtesy of the authorA world ablaze.

Back in Soviet Armenia, in 1940, someone publishes the book “The Culture of Hops” (A manual for hop production foremen). Even in a dying world there exists a professor of hop cultivation who does the editorial work. And, since you are already into monkeying with this memory loss of yours, why not name the professor – no address, just write it down, perhaps he’ll, indeed, survive the exile. Here: Professor E. Antonyan – and who was he? On which street did he live in Yerevan? How exactly did he perform his professorial duties? Did Stalin’s repressions target him because of the hoppy wolf pup? Was he exonerated? Why does death validate the injustice of execution?

Nearly a century later, in 2023, with half the world ablaze, here she is – Zaruhi, clinging to the library shelves, studying the experience of cultivating the hoppy pup from the book that remains unparalleled within the Soviet heritage: “One day wars will stop. There will be no more Putin, Erdogan or Aliyev – they will all crumble to dust, along with those who amassed power through their deaths, who wielded authority over their living corpses. And there will be liberation from the

Besides, I’ll finally complete a documentary on the life story of my maternal great-grandfather, Professor Antonyan, or rather a fictional life story. Someone who managed to edit a work devoted to the culture of hops – that’s it. Executed while in exile – exonerated by death. Did you notice this banality? After 1937 everyone is suspicious of everyone else. People hunt for informers and traitors among themselves, sometimes finding them but unsure how to proceed. Stalinism did know how to proceed.

Every time I order a book from the library about the hoppy pup, it feels as if I’m resurrecting the memory of Professor Antonyan – a cenotaph – an absent place for an absent body. One day I’ll come with you to the Kanaker hydroelectric power station: I want to see the monuments representing prisoners of war.

I came across the news about the war incidentally – right in the middle of twirling my spoon around in a saucer of jam, picking out these pits. It could serve as a good metaphor perhaps, or the devil knows what else. The news completely slipped past me, that’s true, didn’t catch a thing. Just kept on fishing the pits out of the jam. While I was pulling pits out of the jam, soldiers on the border were pulling entrails out of each other – not with a spoon or fork, but with their bare hands. Saw it all on Telegram. Why did I see it? I had deleted Telegram a year ago. Seriously, the jam and the entrails came together by accident. The same scale measures the ice cream on the Cascade, the pits in jam, and the soldiers tearing each other’s entrails apart – what, on earth, am I even talking about.”

Cheap Chinese glue will save – I was about to say – the world … but it would sound stupid, much like all those overly serious statements. Let’s put it this way: Chinese glue will save some dying books in Yerevan libraries. It seems like Matenadaran is the only place with a book restoration specialist. There, libraries lack book restorers. Instead, they should have these bookbinders who end up making the books unreadable. Occasionally the old book covers get swapped with fascinating new ones – Dante’s cover gets replaced by Lady Gaga’s scream snipped out from some glossy magazine, all sleek and satin. These library binders are people of the modern age, so to speak – individuals of a modern mindset. No irony intended – the updated cover of ‘New Life’ is pretty good. It’s not Gaga’s cry from Dante’s world, it’s rather Gaga’s cry to the world of Dante.

Together with Anya, you keep gluing covers, torn pages and endpapers together – some of them even appear as masterpieces. Nobody needs them, not even yourselves. You keep gluing them together absentmindedly one by one. It’s salutary. Something is passing. It passes – it lives – it doesn’t save.

When we met by the bookshelves and started talking, Anya stated: “I am neither a relocant nor a migrant.” She said, “You know what distinguishes a Yerevan relocant from a migrant? A relocant is someone who, while wandering around Yerevan, one day realizes that in their childhood they definitely weren’t squeamish about semolina porridge.” And then she added, “Hold up, don't laugh, the thought is deep enough.” Then she added again, “It might've sounded funny using the word ‘deep’ but, seriously, don’t laugh, well, I’m not your commander, go ahead and laugh. Oh, I'm issuing orders again.”

While you were having your giggles there, the Russian military were probably killing civilians in Bucha and the soldiers of the Azerbaijani army on the top

This ethical and spine-chilling attempt to twist the feeling of guilt in front of those who perished in the war is about you and only you.

Tomorrow at 11:00 in the library

Zaruhi will bring the hoppy pup

she grew it herself, can you imagine?

with her own hands

aram

Translated from Russian by Kun

Belarus

BelarusНапярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusOn the eve of the unknown the Belarusian writer is playing with the past

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusIm Angesicht der ungewissen Zukunft spielt eine belarussische Schriftstellerin mit der Vergangenheit

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusНакануне Неизвестного беларуская писательница играет с Прошлым

20 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaՌուսաստանն օգտագործել է Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի հակամարտությունը որպես իր աշխարհաքաղաքական շահերն առաջ մղելու սակարկության առարկա

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaRussia used the Karabakh conflict as a bargaining chip to advance its geopolitical interests

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaWie Russland im Spiel um seine eigenen geopolitischen Interessen den Berg-Karabach-Konflikt als Trumpf nutzte

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaКак карабахский конфликт стал разменной монетой в российских геополитических играх

12 December 2023 Georgia

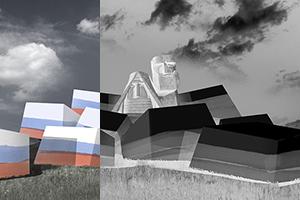

Georgiaამბავი ქართული პოსტკონსტრუქტივიზმისა

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaThe history of Georgian post-constructivism

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaDie Geschichte des georgischen Postkonstruktivismus

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaИстория грузинского постконструктивизма

11 December 2023