Moldova

MoldovaDas schwindende Volk

Ist es möglich, den raschen Bevölkerungsrückgang in der Republik Moldau zu drosseln?

19 October 2023 © Arthur Vakarov

© Arthur Vakarov

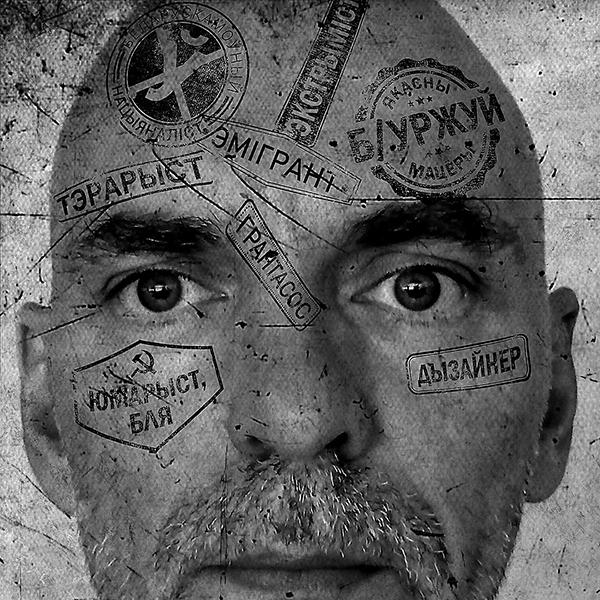

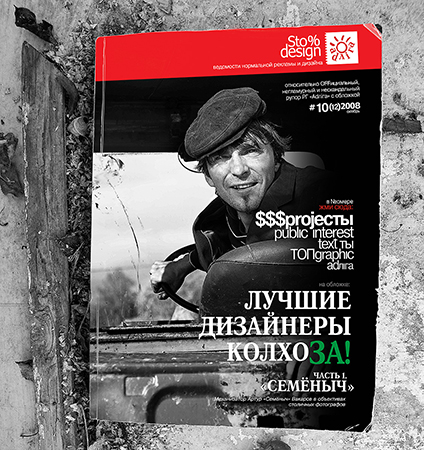

Arthur Vakarov is a renowned Belarusian designer, co-founder of Adliga Studio, director of the vintage furniture shop B/Urzhuaznye Tsennosti, Minsk, author of artwork for a number of national projects, book covers, playbills, posters, etc. In 2020, created revolutionary posters for mass protest marches.

Arthur Vakarov stayed in Belarus until the middle of 2022. After receiving a summons to the Investigative Committee, he decided not to risk his freedom and left the country. Now he’s living in Poland.

OWM asked the designer about his life and his attitude to what is going on in Belarus.

Беларуская English Русский

— Did you have any premonition of the events that happened in 2020? What were you feeling just before summer of 2020 – socially, physically, emotionally?

— I remember well the emotional explosion created by Pavel Belous sometime around mid-spring of 2020. I was developing design for Hodna, and Pasha came by to discuss something with me. At that time Viktor Babariko made the most important decision of his life: to throw down the gauntlet to the dictator. I was desperate, I knew what that decision would cost him: his career, at least, and maybe even his life. For me personally that meant the end of the relatively comfortable life in my cozy Belarus-in-Belorussia. My country-in-country – active, dynamic, Belarusian-speaking, with a population of 100 000 interesting, educated people, with rich cultural life – would be no more. Because of Viktor Babariko’s heroic and senseless act. There would be no more exciting art events, Oktyabrskaya Street [translator’s note: creative area in central Minsk] and the ОК16 culture hub, theatre and film festivals, concerts. “What does he need this big and cumbersome Belorussia for,” thought I. Viktor was the de facto president of my little Belarus: the philanthropist, the sponsor, the initiator, the cornerstone. That’s what I said to Belous. He replied with a bunch of news: about the phenomenon of Tikhanovsky and his Country for Life YouTube channel, about the stirring of the people, the impressive election headquarters, the changes being supported by the business community… I admit I didn’t know much, I was not engaged in parapolitical discours other than as a designer working for social initiatives. At the time, I was skeptically indifferent to the news feed: I knew I wouldn’t miss the top story (may he kick the bucket), and the rest of the news topics seemed to me insignificant and not worthy of my attention. But on that day, as I was listening to Pavel, I began to believe, unwillingly, in the Possibility. A foolish hope got into the head of a Belarusian who had, after many attempts and failures, found a secure place for all his dreams and retired to his cozy Belaghetto.

© Arthur Vakarov

© Arthur Vakarov— So you began to hope for a victory?

— After that conversation with Belous I started following the news. And making forecasts of where the events were leading to. As a veteran of all the previous revolutions, I had a vast experience of broken dreams and post-revolutionary depressions. I saw evil sharpening its fangs in preparation for a fight, not going to let go of power. On the other hand, I saw good spreading its white wings, people beginning to believe in change. Such a situation, in the absence of a total solidarity of the people, could only have ended up in a big and bloody disaster, heroes and victims. I didn’t want to see that once again, that’s why on August 9, the election day, I went to my farm in the naïve hope that I would be able to protect my mind from pain. I had no chances though: the frontline news were impossible to miss out on. And after the horror of the first days of the protest, I saw a miracle: the country was rising. Not the usual 5–50 thousands of brave ones but the entire inert mass. I remember the super-positive shock I experienced when in mid-August I saw thirty something people carrying white-red-white flags in Myadel. In the tiny, quiet Myadel!

© Arthur Vakarov

© Arthur VakarovThen there were the first Sunday marches, the strikes, the mutual aid and the solidarity, I did graffiti at night and design work for revolution headquarters days on end. Even though in just a couple of weeks a new defeat began looming. The unmovable biomass of people never rised. It only nudged a little sending a slight ripple on the surface, and after the first roaring of the villain habitually crept away and assumed the good old posture of “maya hata z krayu” [translator’s note: I can’t be bothered; lit. “my hut is on the outskirts”]. As to the brave ones, the heroes, they, even in larger numbers as before, can be done away with by evil very efficiently.

I fought as a partisan until summer 2022 when they came for me. I fought without hope or sense, simply to let myself feel I was alive and normal.

— How did you live the two years before you left?

— After 2020, Belarus very quickly travelled the distance from being a kolkhoz to becoming a concentration camp. There was no need to invent something new: all dictatorships went in this direction after defeating revolutions. The reaction. Generally, conservative dictatorships always react in a cruel and primitive way. Our evil is not a modern one, brightly-coloured and innovative; it’s a mainstream evil of oldtimers who suffocate with dullness and stupidity. Today in Belarus (and in the RF, and in China, and in Venezuela…), what the regime targets for destruction is not its political opponents but any manifestation of thought, critique, independent creativity. The majority of the political prisoners are not political activists but simply decent people.

© Arthur Vakarov

© Arthur Vakarov— What did you leave behind in Belarus?

— I left behind my Motherland. Not an imaginary land of ancestor warriors, not woods, fields and forest glens, not a Glorious Motherland, not winding paths and tender breezes. The one I left behind does not speak big words. It’s the life I built. The existential value of my path is that it leads to my home. The rest of Belarusian paths are no different to Georgian or Polish ones.

The space delimited by state borders and called Belarus, is an abstraction to me. Likewise, the population of this territory, the population that of its own accord, merely out of the intrinsic aversion to thinking, speaks the occupant’s language. The borders get blurred and so does the notion of a pompous Motherland. By default, it just a territory; it’s the owner who makes it his, who makes it warm. My Motherland is my projects: cultural, entrepreneurial, economic. My part, my communication, my weight in a society.

I made attempts to move into a more positive territory since the cleanout of Ploshcha in 2006. But Motherland would not let me go. I felt cozy among the beautiful hand-made scenery – my B/Urzhuaznye Tsennosti [translator’s note: lit. “second hand bourgeois values”], my design work, my farm, my art – and my people.

The villains robbed me of everything. Looks like I’ll have to build everything from scratch. Or wait hoping to return. A classical Belarusian dilemma of all times.

© Arthur Vakarov

© Arthur VakarovTo be perfectly honest, I can’t understand the stereotype that the best revolutionary is the one who has nothing to lose. In fact, it’s the other way round: why risk if there’s nothing to lose? It’s more secure to emigrate and build upon a steady humanist and progressive foundation. Revolutionaries are us, those who defend what’s already built. I can hardly believe I could build anything as good as that once again.

— Is there anyone in Belarus you worry about? Why did they choose to stay?

— The uncertainty of emigration is scary but going back behind the barbed wire – mental and physical – a lot scarier. I feel really sad for people who stayed there. This sadness is felt as awkwardness and sympathy – the aftertaste of conversations with those still in the concentration camp. I know how hard it is to decide to leave the country. I wanted to do it for years but always had doubts and would always decide to stay. Until the moment the dissident/émigré alternative changed for the prisoner/émigré alternative. Recently, I’ve been speaking and arguing a lot with the last partisans. The same reasonable arguments: age, family, money, projects. These things are important but one has to look at the processes soberly and foresee the scale of the imminent collapse. Dictators are frightened, they’ve already transgressed the limit of humanity: war, terror, man-made disasters – we are already seeing these today, and these are going to be yet worse tomorrow.

© Arthur Vakarov

© Arthur Vakarov— Is it possible and necessary to give advice to those who chose to stay? What can we really do for them from abroad?

— I am pleasantly surprised and inspired by the phenomenon of Belarusian solidarity! I am impressed by the unity of the new heroes. It’s the first time I’ve seen it: before, defeated protesters would crawl back to their holes to lick their wounds. Today’s solidarity gives you the feeling (a strange one) that we did not lose the battle completely but only retreated from the battlefield, so to speak. That we somehow saved the army and the flag. The moment you’re summoned to the Investigative Committee all you feel is confusion and fear. But you make a couple of calls and you’re no longer alone, you get helped, directed and rescued. When, safe, you find yourself alone, without money, family and job in a foreign country, you’ll get helped again. And again, and again, until you’re sorted. I thank for the help BYSOL, BY_Help, Belarusian House, the Belarusian Solidarity Center… I thank my friends who, despite their own problems, gave me their support, fixed me up and blew away the clouds. Solidarity is the most important thing on the way to a new, real, humane nation. An archaic evil won’t stand a chance against solidarity. It’s logical that now I’m helping those fleeing repression.

© Arthur Vakarov

© Arthur Vakarov— What difficulties have you been facing as an émigré?

— The ambiguity and unpredictability in legalisation don’t let you get settled. Little depends on the little man. The bureaucratic machine of migration institutions even in the most advanced countries is unpleasant and low-maneuverable, it doesn’t stop and gives no respite. It’s a factory of standard yet unpredictable decisions. You, clearly, can’t afford to sit around and do nothing waiting for a piece of European plastic. At the same time, your options are limited to operational and short-term issues.

Nevertheless, the most important thing is to believe that you can still achieve what you want to achieve, that you still have the strength and courage to start new meaningful projects.

© Arthur Vakarov

© Arthur Vakarov— How did you and your family adapt to new conditions and countries?

— We went first to Georgia. The country, undoubtedly, made a huge step forward since I last visited it in 2009. It’s evident that some brain and money have returned from the emigration forced by the Russian aggression of 2008. Today’s Georgia shows signs of moving towards the European civilisation. But from the strategic point of view, Georgia does not look a good option to consider as a new (and, possibly, last) centre of my life. Firstly, I don’t want to even imagine a situation in which I would have to flee again. And the danger of a second Russian Fascist invasion is still high. Once defeated in Ukraine, Putlerism may look elsewhere for an easier victory to uphold its reputation and rekindle the popular euphoria. Secondly, I got a little tired of “young, stupid and hungry” post-Soviet peoples. Of the endless self-affirmation and showing off, the lack of taste and measure, the cult of cars and consumerism, the greed and arrogance. All my life I’ve been an internal émigré in my Belarusian ghetto – it would be foolish to change it for a Georgian one. And, for that matter, it’s impossible to be accepted by the locals. Whereas it’s difficult but possible to become an ordinary European everyman.

That’s why I’m in Poland now. Returning to Europe after two and a half months in Georgia was almost like coming home. The mentality, the weather, the people, the attitudes – everything is so logical and acceptable. It doesn’t even matter what country I’m talking about – the supremacy of the principles of democracy, humanity and human rights would be enough for me in any corner of Europe. The life in the Belarusian corner will be just as comfortable when the majority of Belarusians come to their senses and dethrone the evil relic.

© Arthur Vakarov

© Arthur Vakarov— What do you think about the accusations, in connection with the war, that Belarusians are collectively guilty? Have you felt the consequences and how do you respond?

— It’s a totally new feeling. It really hurts, it’s unfair and terribly painful. I’ve always been sympathetic towards normal Russians who have to share responsibility with the ignorant and aggressive biomass of their compatriots. Before February 24, it was enough to simply say, “I’m not Russian, I’m Belarusian.” And no further questions would arise. But then I became an aggressor, an enemy, a conformist. That’s not me, of course, that’s my passport but who bothers to go into detail these days. So I had to try on the cholera clothes of a hostage of the majority. Undoubtedly, the most serious crime of the kolkhoz führer is smearing with blood of the good neighbours my people – most unaggressive, tolerant and peaceful people, the hobbits of Europe.

Painting an individual the colour of his passport is, obviously, a foolish anachronism. Evil, in this stretch of history, arose in a country I didn’t choose at birth. My whole life I’ve fought and risked all that those who criticise me now because of my passport can never experience. It is clear that neither a reasonable European nor a reasonable Ukrainian will resort to self-assertion in such a primitive manner. Flashing around your passport is kind of an oddity from the past century.

— How do you keep sane in the midst of insanity?

— It’s not easy. Gloom and lack of hope don’t make it easier. As well as the constant fear: for yourself, for your loved ones, for your projects. To stay positive you have to be a simpleton or a superhero. I am neither. My internal spiritual shelter didn’t survive a direct hit. That’s why I left. There’s more light where I am now. I had hoped to dive into art, books, films, vinyls and sit it out in my forest scraping up some simple human joys. But, as it turned out, in the 21st century you can’t hide in Belarusian woods.

Translated from Russian by Alexander Stoliarchuk

Moldova

MoldovaIst es möglich, den raschen Bevölkerungsrückgang in der Republik Moldau zu drosseln?

19 October 2023 Moldova

MoldovaWie die Opposition in Moldau neu zusammengesetzt wird und wie sie sein wird

11 October 2023 Belarus

BelarusDer Winter wird lang, aber wir können einander wärmen

4 October 2023 Moldova

MoldovaWie Chișinău im 20. Jahrhundert zum Schauplatz eines toponymischen Desasters wurde

2 October 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaÜber Gedächtnis und Traumata der modernen Welt. Der armenische Autor Aram Patschjan spricht aus den Räumen einer vergessenen postsowjetischen Bibliothek

26 September 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaGeschichte und Herausforderungen des unabhängigen georgischen Films

25 September 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaDer Kampf um Freiheit im Schatten des Hungers

11 September 2023 Belarus

BelarusEine belarussische Schriftstellerin über 300 Jahre Meinungsunfreiheit

8 September 2023 Moldova

MoldovaNicoleta Esinencu über die unangenehme moldauische Realität, die gern ignoriert wird

4 September 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaAnmerkungen zum Streik der Bergleute in Tschiatura

31 August 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaJerewan verliert seine Erinnerungen – und die Zukunftsperspektiven sind unklar

17 August 2023 Belarus

BelarusSkizzenhafte Gedanken und Zitate über eine außerordentliche Ästhetik

11 August 2023