Belarus

BelarusЖыццё пад сталом

Напярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 Nicoleta Esinencu (centre) with the theatre collective Spălătorie© teatru-spălătorie

Nicoleta Esinencu (centre) with the theatre collective Spălătorie© teatru-spălătorie

The government in Moldova may be

Română English Русский

In 2023, independent Moldova turns 32. This is an age at which one can be expected to understand something about oneself and about the country too. Unfortunately, the most important thing that is becoming clear now is that Moldova does not want to live independently. We always need someone who would come and tell or show us how to live. We still cannot define what we want and what we strive for.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union this did not become a major subject for discussion. I would venture to say that it did not become a subject at all. No one raised the question of whether we can decide for ourselves how to live; whether it is necessary that visitors from both the East and from the West should tell us how to live; whether it is necessary that we should borrow money from everyone only to have to repay it later on; whether it is necessary that we should live in debt?

In the modern world, especially recently, it has become very fashionable to talk about decolonisation. In Europe, in the West in general, they like talking about it because they suddenly found someone worse than them: the Russians. This is a fashionable subject but still there is no serious discussion.

I hear this message, “Let’s talk about decolonisation but let’s not talk about ourselves.” As if the period when the West colonised half the world did not exist. It is believed that the West resolved this issue, that it dealt with the (to put it mildly) less savory chapters in its own history. And if our issue has been resolved, let us talk about others. Let us talk about Russia and let us finally help Eastern Europeans resolve their issues.

But hold on, I still have some questions. How did you resolve this issue? Did you return everything you had taken? Did you stop looking down on and placing yourselves above others? Did you change the perspective in your textbooks, in your museums, in your literature, in your policies? Of course you did not! And your own past still needs to be understood and worked through. As to our issues, leave it to us to decide how to deal with the colonisation/decolonisation of our countries, with the imperialism in the East. This is our history.

Germany or France would hardly be pleased that the USA tells them what to do with their past, with their history. Likewise, we are unhappy that someone – be it Russia, the US, the European Union, or the World Bank – tries to lecture us, condescendingly, on what we should do. Maybe using the term ‘us’ here is a bit of a stretch. OK, I will not speak for everyone, I will speak for myself: I don’t like it.

Today the term ‘decolonisation’ exists, it is used, everyone is talking about decolonisation, but what does it mean? Does it mean that people must decide their own fate and make their own history, or does it not? This is an elementary question. But it is yet to be answered.

Moldovan politics fails to give an answer either. In Moldova, we are used to always having to vote against someone in elections, not to vote for some values but against some politician. There are two sorts of shit on the political menu: let us choose one that stinks less. But wait a minute, can we have some values please? Or are we forever doomed to choose from the two evils?

Today we live in a country where you cannot criticise the government. Our government is

And they lecture us on European values, which creates a resonant dissonance that further generates new questions. What values do you choose, folks? What do you know about them? What does the exploitation of labour migrants in the West have to do with these values? How about the boat carrying refugees left to perish in the Mediterranean? Or is this the part of a story that should not be told because it would be unpleasant? The situation is similar to that of the Holocaust. In Moldova where it happened and where in Soviet times deportations also took place, it is more pleasant and comfortable to speak about deportations. But, excuse me, one does not eliminate the other. You should speak about everything, you cannot pick only what you want and ignore everything else.

When in 2021 our theatre presented the Clear Story performance about the Holocaust in Bessarabia, I saw that the public were shocked. Young spectators were coming out of the theatre building saying, “Oh, this happened in my grandma’s village, and no one ever told me about it!” At the same time they regard Marshal Ion Antonescu as a hero. In our history textbooks to this day it is written that Antonescu was a controversial figure. To this day they say that during World War II the Romanian Army liberated the territory of Moldova. Do you understand that we were liberated by Fascists? I think these are very simple things that cannot be misinterpreted. Or can they?

Our theatre is a political theatre. Politics is what creates our life, and for me personally it is definitely very important. If you as a modern person ignore political themes, then you make believe you do not exist in modern society. But uncomfortable questions will get you at some point. You cannot erase what you do not like in the past. That way, you risk accidentally erasing yourself, the history of your parents, and in the end the history of your country.

Today these uncomfortable questions about our past and present (sadly there is almost no discussion about our future) have become yet sharper and now they are cutting us like a knife. The war is being waged just over there, across the river, and it cannot but affect us. We stopped struggling for peace or speaking about peace, now we are speaking only about armaments. We are living in the times when peace has fallen out of fashion. We are watching the war from the sofa as if it were a video game,

Our divided society is getting divided once again: by itself and by the politicians. It would seem we should have understood long ago that we are all very mixed here. In Chişinău at the beginning of the 20th century there were over 40% Jewish residents. My mother comes from a Ukrainian family, my father from a Moldovan one. But instead of crossing these cultural divides, with our different languages interweaving into a common wealth, we prefer to create divisions among ourselves and among other people.

The long-forgotten (or so I thought) rebuke is heard again, “Why don’t you speak Romanian?” I did not even realise that we are still caught in this language trap. It is a nationalism that is phase by phase being born out of ethnicity. It is when, as a Russian, you tell a Moldovan how they should live, and the Moldovan says this to you.

The Republic of Moldova is a country half of whose population (or maybe more) has gone abroad for work. They are migrants and Moldova survives only because they are working somewhere else and sending their money home. We produced two shows about Moldovan migrants. We did it in the West, in Germany. The shows are based on scores of interviews with Moldovans working abroad: in Germany, in Italy, in Great Britain, in France.

In Moldova, everyone has a relative or at least an acquaintance who went abroad to earn a living. I know

In Moldova, the government remembers about the migrants for a short while before the elections. And then we hear, “Our diaspora is our pride!” We hear some stories, ‘success stories.’ What success stories? What pride? An overwhelming majority of those who work abroad do not have and will not have any pensions there, neither will they have benefits in their home country. Who cares what will happen to them tomorrow and what they will live on when they are no longer able to work? There is no law to protect them, and no one cares that there is no such a law.

We wanted to create and we have created a theatre about humans, a theatre focusing on humans and human problems. We founded Spălătorie theatre in 2010. The first venue for our project was a laundry, spălătorie in Romanian, so we chose this word as a name for the theatre. We received virtually no funding from the government. We looked for grants, we borrowed money. Then we started going to Germany and producing our shows there.

Now it is in Germany that we have our main base. The Germans happened to be interested in what we do. Our compatriots did not. In Chişinău, we have not had a space to rehearse and produce our shows since long ago. Why is that? My guess is a theatre like ours is simply not needed. We talk too much about the rights that are not respected: about women’s rights, about gay rights, about the rights of those who are weak, about the rights of workers. We raise uncomfortable questions, we talk about unpleasant moments in our history.

Everyone is better off without the likes of us, I have no other answer. But we exist. Just like those we will continue to talk about no matter what. Watch out!

Translated from Russian by Alexander Stoliarchuk

Belarus

BelarusНапярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusOn the eve of the unknown the Belarusian writer is playing with the past

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusIm Angesicht der ungewissen Zukunft spielt eine belarussische Schriftstellerin mit der Vergangenheit

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusНакануне Неизвестного беларуская писательница играет с Прошлым

20 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaՌուսաստանն օգտագործել է Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի հակամարտությունը որպես իր աշխարհաքաղաքական շահերն առաջ մղելու սակարկության առարկա

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaRussia used the Karabakh conflict as a bargaining chip to advance its geopolitical interests

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaWie Russland im Spiel um seine eigenen geopolitischen Interessen den Berg-Karabach-Konflikt als Trumpf nutzte

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaКак карабахский конфликт стал разменной монетой в российских геополитических играх

12 December 2023 Georgia

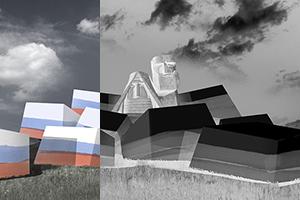

Georgiaამბავი ქართული პოსტკონსტრუქტივიზმისა

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaThe history of Georgian post-constructivism

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaDie Geschichte des georgischen Postkonstruktivismus

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaИстория грузинского постконструктивизма

11 December 2023