Belarus

BelarusЖыццё пад сталом

Напярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

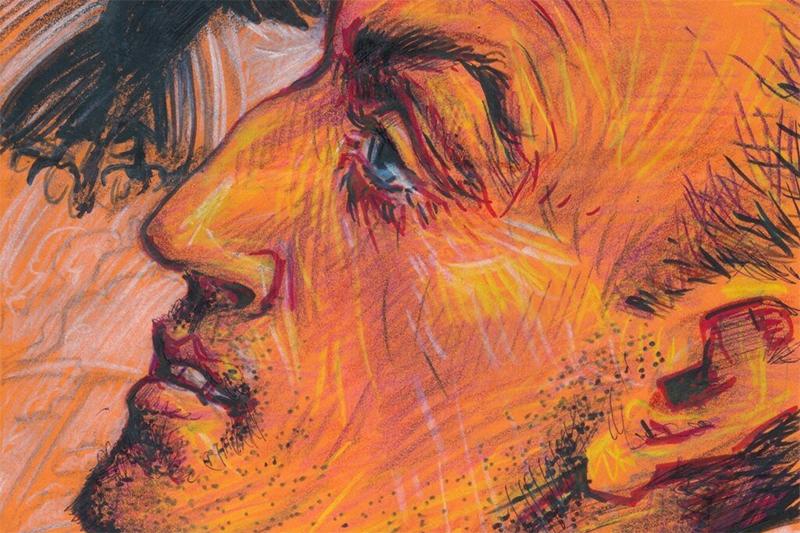

20 December 2023 Ales Pushkin. Prison self-portrait© Human Rights Center Viasna

Ales Pushkin. Prison self-portrait© Human Rights Center Viasna

Partisan art is a purely Belarusian invention. When your town is captured and publicity is punishable. When TV vomits hatred and political prisoners are killed in jails. When you’re denied a say but allowed to run away. With any luck you’ll be let out of the country. With yet more luck you’ll be able to come back. And not regret it. It is vitally important to clean up your phone. To filter down your contacts. It is a habit of yours to start at the sound of a car door slamming near your house in the morning. While someone builds his career and goes to Crimea for some sun. Now imagine in the heart of Europe something of the kind lasting, with short remissions and regular relapses, for a quarter of a century. How can you be an unfettered artist? How can you be free and proud? Especially if you happen to be Stierlitz, Cheburashka and Kazimir Malevich rolled into one.

Беларуская English Deutsch Русский

“You’re a rock ’n’ roll suicide…”

David Bowie

I

The recent death of Belarus’ main political art prisoner, artist and performer Ales Pushkin gives us an occasion to speak about the special type of creative personality raised and formed by the Belarusian regime because his story reveals with utmost clarity the strengths and weaknesses of Belarusian art activism and intellectual resistance.

Let us begin with two obvious points. Firstly, Lukashenka’s stagnant quasi-Soviet political regime was only capable of creating (and created) a quasi-Soviet cultural policy model commensurate with its power and its nature. Secondly, a quasi-Soviet cultural policy model in a country of an unfinished democratic transition could only have an alternative in the form of similarly (anti-)Soviet cultural dissidence. Aesthetic protest, formal deviance with no chance to win. In the case of Belarus two defective tactics clashed: the soft servility of the moment and the stubborn Bohemian ‘partisaning’. Two applied design options. Two yesterday’s stories.

One fundamental similarity between them is that neither was able to change the country and the people on its own (without political leverage). One fundamental difference is that servility was supposed to raise obedient loyalty while partisaning was supposed to raise colourful dissent.

Ales Pushkin: ”Art is necessary to only a few. But if those few really find it necessary, they understand everything. It is, after all, they whom I address.” (2004) [∗]

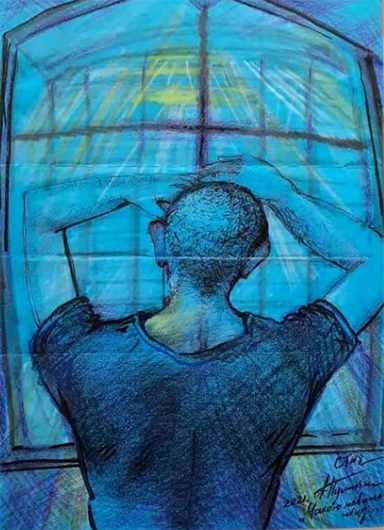

Ales Pushkin. Prison drawing© Human Rights Center Viasna

Ales Pushkin. Prison drawing© Human Rights Center ViasnaII

In the early 1990s in the cultural field of the newborn Belarusian independence two performances were enacted that corresponded to the two types of cultural activism: servile-passive and passionate-hyperactive. The potential of both turned out to be greatly exaggerated.

Yes, the nation could not be saved by tours of Russian pop singers, spy films about aviation secrets, police novels by Mikalay Charginets or the provincial frenzy of the Dazhinki harvest festival. But likewise the nation could not be saved by Lavon Volski’s rock songs, Valentin Akudovich’s philosophemes, and Ales Pushkin’s daring performances.

The drama and desperate beauty of the early Belarusian alternative art is that it invariably operated as a factor of change even when other factors were nowhere to be seen. Its main and indisputable advantage was the unofficial creativity, the desperate need to “think Belarus” (in the words of philosopher Uladzimir Mackievič sentenced to five years in a high-security prison). The main disadvantages were its very limited conceptual and stylistic resources.

The new country was not being built but dreamt, assembled from what was available: homegrown philosophy, mosaic education, the interwar chanson, scraps of information about foreign art practices, the Soviet dissidence, the Polish radio, the émigré press, provincial chic, and partisan courage. And it felt quite comfortable in the familiar niche of exercise in mental design, in the territory demarcated by such rock ‘n’ roll national romantics as the “Niezaležnaja Respublika Mroja” [Independent Republic of Dream, a cult Belarus rock band], in the zone of the common dream. Its main success was the very fact of its existence, its main prospect was maintaining its partisan status.

Ales Pushkin: ”I once had a Russian cellmate who’d lived in Belarus for 17 years. He told me that I had to speak Russian to him. I replied that Belarus was my land where a Belarusian-speaking Pushkin was a reality he would have to put up with.” (2012)

In the field of unofficial creativity, boundaries between the awakening of the nation, civil activism, artistic work, and political action were merely conventional. For this reason, both sides of the ideological confrontation would often think they did not exist at all. Politics was performance, performance was politics. Rock music played at clubs rocked the regime, a painting on a street display helped unbrainwash the public, translations of Nobel Prize winner Alexievich's books into Belarusian offered a direct challenge to the authorities, private art galleries were socially dangerous. So keeping hold of the political field required a victory in the cultural field. And vice versa.

Needless to say that all the involved parties were proved wrong victory-wise.

Some believed in changes as a performance. Others turned out to be ready to kill for it.

Ales Pushkin. Prison drawing© Human Rights Center Viasna

Ales Pushkin. Prison drawing© Human Rights Center ViasnaIII

Previously, everything was clear: inside was the underground, outside was the parade.

In the times of relative stability partisan art acted according to circumstances. It operated in a sleepy country under an oppressive regime in the only possible way, through public clowning, cunning metaphors, showman’s attractions, encrypted messages, and

But what other way was there to move the country and themselves forward without an open culture or civil liberties?

You should jump up to make them see you. You should set yourself on fire to make them warm.

Ales Pushkin: ”The participation of poet Uladzimir Nyaklyayew in the 2010 presidential campaign was a performance, a performance of a creative person like me. I am also planning to run for president in 2015. Ales Pushkin, a Presidential Candidate. When the time comes, you will see this art project of mine.” (2010)

Only freaks would survive, buffoons of our nezalejnasc [independence].

And only as long as the regime was interested in playing with vyshyvankas [traditional embroidered shirts].

Ales Pushkin. Prison drawing© Human Rights Center Viasna

Ales Pushkin. Prison drawing© Human Rights Center ViasnaIV

The authoritarian Belarus was and has been up to this point a country of lots of ‘withouts’: a country without a real multiparty system and political competitiveness, without efficient

A shout out of the window. An art installation. A freak parade. A visionary experiment.

A performer's gesture rather than civic action.

You can come to the square in front of the president’s office building ... for two minutes until you get detained ... get arrested under criminal law ... spend 24 hours in a prison cell ... be released ... and get arrested again ... and be released again. So that for the general public your story would shrink to the size of a joke, ”Pushkin? The one who brought Lukashenka a cartful of manure?” In the conflict of the concept, the content, and the context, the inevitable winner has been the context.

On our block, they just don’t get it about your actionism!

Ales Pushkin: ”We’ve been living in Bobr for 13 years, and today I can state a fact: people don’t need a freedom cry, their souls don’t respond, don’t resonate. I am the only professional artist among 32 thousand Krupki district residents, but even one artist seems to be too many for them. What do they make of me? To them, I’m a foul-mouth, rascal, and bandit. When on Kupalle night [summer solstice holiday] I brew krupnik [traditional alcoholic drink] and give it out to people, I wouldn’t be surprised if I get accused of moonshining and the illegal sale of alcohol. The moment these charges materialise I’ll know I’ve turned into a complete village rascal.” (2016)

A provincial partisan is always touching and funny because his war is incomprehensible to his neighbours. That is why he will often feel that he fights a lonely battle as he tries to save a country that just doesn’t care.

Your country will eat you up. And you will keep coming back to your motherland anyway. To be massacred.

This is the choice. This is the mission. This is the Motherland.

While you’re burning, people will queue for beer. But here’s the thing: you can’t help doing it.

In fact, they can’t help doing what they do either.

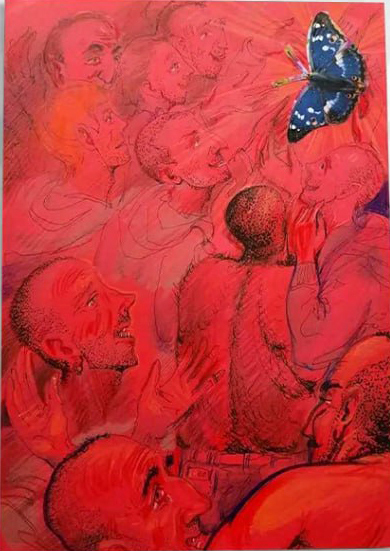

Ales Pushkin. Prison drawing© Human Rights Center Viasna

Ales Pushkin. Prison drawing© Human Rights Center ViasnaV

At the heart of the situation lies the increasing divide of perceptions. In the sharp conflict between different public spectacles where one performer relies on the beauty of gesture, and the other on beating the opponent into the ground.

The underside of partisan art is its doomed and inspired victimhood. A partisan can’t win. A partisan can’t surrender.

Ales Pushkin: ”I am an Orthodox Christian. And it is based on this that I don't feel sorry for myself. For the Scripture says, 'It is through suffering that I will be washed clean, it is through suffering that I will be made white.’ People will believe me more if I walk on the snow barefoot than if I used а mannequin instead or spread straw where I’m going to fall… Only faith and some sort of Oriental frenzy of mine are what make me a walking disaster of a man, a performing artist.“ (2002)

This could be a scene from a 1950s American film: two cars on a night highway are heading straight towards each other, whichever turns away loses. In Pushkin’s case, both decided to go all the way. Right to the end.

Could things have been different? No. Not in this old-fashioned film.

Here everyone is a hostage to the script. Everyone performs his part in full.

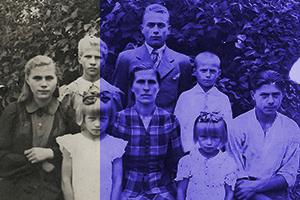

Ales Pushkin. Mother of God Mourning

Ales Pushkin. Mother of God MourningVI

Ales Pushkin’s death marked the final decline of the age of permitted liberties, the destruction of old convenient conventions, “You can frolic down below while we rule here at the top!” The regime is reeling. The system is being hysterical, it is surviving on denunciations and imprisonments.

You can still drink your ristretto on a summer terrace, you can still get invited by referral to an apartment exhibition and pretend for a couple of hours that everything is OK. But the visible regular presence of unofficial art in the public field must be forgotten once and for all.

The regime is driven by the logic of a schoolyard bully, “I’m gonna get those weaklings first, then those

Right before our eyes, an emergency cultural regime is being implemented. No sentiment now. Everything has become tighter: your art is your fear. Charges will be made against anyone.

The artist hunt in today’s Belarus is a new incarnation of the old totalitarian practice: weeding out aliens. It's the kind of mortal aesthetic incompatibility that can transform semantic differences into cultural terror with lethal consequences.

Ales Pushkin: “I felt I had a moral right to say that our state was of a

The war of cultures went off to war on culture. A strange artist, an informal patriot is no longer a marginal weirdo but an open enemy, a political opponent. The government is no longer a dad to everyone but a sadist and butcher who now has an acute fear of the artist as an equal.

But we’re not equal. We have different instruments. And different power resources.

Things become clear when OMON [riot police] goes out to meet the artist.

There is no place for good alliances and successful outcomes.

There is the simple dilemma: either victim or executioner.

From now on entering the cage to play the tune in the old way is tantamount to suicide.

Ales Pushkin. Day and night. 2014© From a private archive

Ales Pushkin. Day and night. 2014© From a private archiveVII

It is time to look back at the played-out scene.

The generation of art partisans at the beginning of Belarusian independence are our Galactic Heroes, a team of target application progressors [translator's note: In science fiction novels by Soviet writers Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, the noble and self-sacrificing supermen who advance progress in clandestine operations on other worlds] brave yet very Soviet in some respects. A flying squad of national design fixers with the naïve faith that creativity would shake up the country, that grey colour was better than red, that Belarus lived inside a dictionary, that rock ‘n’ roll would save you from ‘Moscow in your head’, that style would cure stupidity.

The romantic national performance is a first rate vanishing breed that invites talking paradoxes.

They were avant-garde without rearguard. The wonderful hopeless. The beautiful. The desperate. The undesired. The experimenters of Minsk vintage. The children of Van Gogh and Dali pocket-sized art books. Improvisational politicians. Icon painters and restorers. Visionaries and idealists. Samurai of the adradjennya [Renaissance]. Sketches of an impossible tomorrow.

Belarus happened to have had a culture of daydreamers and dandies, connoisseurs of pagan ethno, German industrial music, French post-modernism, applied Buddhism and Polish punk rock. They were fundamentally incompatible with the kolkhoz [collective farm] regime and the provincial supporting cast.

They had a plan for the country. But they had no country for the plan.

And the Motherland let them go. Those who managed to survive.

The motley games were over. Time was broken. Again.

The project is dead. The daydreamers burned out.

Now it’s time for Orthodox special forces, art martyrs, and last-minute migrants.

Do you want a new country? Make sure that all of these be non-existent.

[∗] The text contains quotations from various Radio Svaboda interviews with Ales Pushkin.

Translated from Russian by Alexander Stoliarchuk

Belarus

BelarusНапярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusOn the eve of the unknown the Belarusian writer is playing with the past

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusIm Angesicht der ungewissen Zukunft spielt eine belarussische Schriftstellerin mit der Vergangenheit

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusНакануне Неизвестного беларуская писательница играет с Прошлым

20 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaՌուսաստանն օգտագործել է Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի հակամարտությունը որպես իր աշխարհաքաղաքական շահերն առաջ մղելու սակարկության առարկա

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaRussia used the Karabakh conflict as a bargaining chip to advance its geopolitical interests

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaWie Russland im Spiel um seine eigenen geopolitischen Interessen den Berg-Karabach-Konflikt als Trumpf nutzte

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaКак карабахский конфликт стал разменной монетой в российских геополитических играх

12 December 2023 Georgia

Georgiaამბავი ქართული პოსტკონსტრუქტივიზმისა

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaThe history of Georgian post-constructivism

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaDie Geschichte des georgischen Postkonstruktivismus

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaИстория грузинского постконструктивизма

11 December 2023