Belarus

BelarusЖыццё пад сталом

Напярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 © JAMnews

© JAMnews

We present to our readers an article by anthropologist and member of the “Khma” (“Voice”) socialist movement Giorgi Khasaia about the strike of miners from the city of Chiatura held in front of the Georgian parliament building in Tbilisi. The author believes that this strike set an important precedent: for the first time in the history of protests in post-Soviet Georgia, the voice of the working class was truly heard and its interests were expressed.

We chose to publish this article for several reasons. First, unlike most Georgian media, we consider it important to present the entire spectrum of democratic political and social thought in Georgia, from socialists to libertarians. Second, we aim to cover not only the surface-level social, political, or cultural processes but also, and in particular, those that receive little attention yet are of growing importance, in our opinion. We anticipate that social protests in Georgia will gain momentum over the coming years, especially since Georgian workers now need to fight for the rights that their counterparts in EU countries have enjoyed for decades. In Giorgi Khasaia’s column, analysis and activism are inextricably linked, and this is precisely what makes his article utterly relevant.

ქართული English Русский

On a screen installed in front of the Georgian parliament building, the Chiatura miners displayed the footage they had taken on their cell phones, showing their work and employment conditions in the mine. In these videos the miners are depicted manually moving

This footage leaves a painful impression and prompts one to think whether Georgia itself has turned into a hollow, loosely shored up and unpredictable mine that generates fear for the future. This mine still contains wealth, which however, belongs to the capital constituted by some LLCs [limited liability companies], whose interests are intricately linked to those of government officials.

The miners of Chiatura went on labor strike in early June and put forward fourteen demands, including, among others,

Chiatura is an industry-specialized city, whose economic vitality depends on a singular type of production and where daily life is fundamentally determined by the miners’ salaries. Due to these factors, the miners’ protests are typically met with a genuine sense of solidarity from their fellow citizens. Throughout the strike, teachers and students joined the miners’ marches, while

For both Chiatura and the broader Georgian industrial working class, strikes are not unfamiliar occurrences. But until this point all strikes had taken place in proximity to the mines and within the areas where the production process is localized. Strikes started and ended within those cities. This time things were different. The miners occupied a politically significant space for the nation – the area in front of the Georgian Parliament building. This space was historically where political crises would begin, where governments would be compelled to make concessions, or even where resignations would occur. Yet, never before had the working class spoken from this space. Never before had it voiced itself as a subject with agency, which, while lacking its own political body as of yet, refrained from attempting to colonize someone else’s domain, as is often the case. In all previous

One could argue that, perhaps, all large-scale actions held in front of the parliament building had been under the influence of the collective mindset of the middle class. Accustomed to organizing urban protests, the middle class had acquired a sort of exclusive right to this space, along with infrastructural advantages and a network of interconnections. I am not suggesting that the middle class constituted the majority at all significant protest rallies. Physically it was actually in the minority as, for instance, during the March actions and demonstrations against the

This time around, a different voice was heard, a different speech, a different type of public expression was presented and it was private property that became the target of the attack. As the protest campaign unfolded, class and national issues naturally converged. For the first time, the call for nationalization was raised during these actions, a demand that is rarely articulated by the workers. In his speech at the rally, Simon Mikatsadze, a miner, stated: “We need to demand the nationalization of natural resources. Profit should benefit every Georgian, making retirement social security better and giving a good life to the next generation, not just that of the capitalists.”

As historian Ronald Grigor Suny wrote, in the 19th century Georgia discovered, in one way or another, the solutions to its problems through socialism, rather than nationalism or liberalism. That choice was a historical outcome of the specific social context and intellectual environment in which all three movements arose.

The emerging capitalism was already giving rise to the industrial bourgeoisie and, naturally, the proletariat. Simultaneously, another factor played a crucial role in the convergence of class and national struggles. During the process of proletarianization, the Georgian working class in urban areas encountered both Russian bureaucracy and the Armenian bourgeoisie. This intersection initially gave rise to an egalitarian classless nationalistic ideal, which only later evolved into connotations of a class dimension under the influence of Marxist thought.

History rarely provides the working class with a prearranged set of circumstances perfectly suited to its needs. In today’s Georgia, things are not the same as they were at the beginning of the last century; nonetheless, it remains important to delineate the scope of nationalization as such. The matter of natural resources takes on a new significance for Georgians within the context of the convergence of class and national issues. This process began with the Namakhvani movement (a movement against the construction of the Namakhvani hydroelectric power station), which emerged primarily due to land use concerns. The issue of natural resources is intertwined with the land challenges and the activation of one inevitably triggers the activation of the other. For instance, the timely halt of manganese mining in Chiatura leads to the stoppage of the Zestafoni Ferroalloy Plant, subsequently affecting the process of coal mining at the Tkibuli mines as well.

Alongside this, the process of Georgian privatization, especially following the Rose Revolution of 2003, was orchestrated by Kakha Bendukidze in a manner that resulted in the transfer of Bolnisi’s copper and gold deposit occurrences (which have been the primary export commodities from Georgia in recent years), as well as a significant portion of the energy infrastructure and other vital assets, into the possession of Russian capital. Within this context, opposition to Russian imperialism in Georgia, largely manifested through bourgeois nationalism, could gain a proper perspective by highlighting a class conflict. Meanwhile, the local bourgeoisie is extremely retrograde, a fact that Georgians experience on a daily basis – for instance, in sectors like pharmacies (which are entirely controlled by local businesses) and banking.

The history of manganese mining in Chiatura dates back to 1897. Fifteen years later, the Chiatura manganese mines were connected by rail to Zestaponi, and from there to Poti; thus, manganese became an export commodity. In 1913, a million tons of manganese was exported from Chiatura through Batumi, accounting for half of the global market. According to the universal law of capital accumulation, where capital amasses at one pole, poverty accumulates at the other and so, as expected, in the same year one of the largest and longest strikes in the entire history of Chiatura took place.

During the First Republic (The Democratic Republic of Georgia, which existed from 1918 to 1921), the social-democratic government granted the Germans the right to utilize all ships in Georgian ports, along with a monopoly on ore extraction and export. In 1920, Germany, on which the Georgian government had rested high hopes, signed a peace treaty that ended the First World War. By 1920, manganese production at Chiatura had declined

In 1921 Lenin made inquiries, along with the Revolutionary Committee of Georgia, seeking confirmation as to whether the Soviet government of Georgia had already approved the concession of the Tkvarcheli mines to the Italians and whether the German owners of the Chiatura manganese mines had changed their status, specifically whether they had become concessionaires. Lenin had written that concessions with Italians and Germans were of particular importance along with the exchange of oil for various goods. Concessions, as a form of cooperation with foreign capital, were necessary for the Soviet Union to restore the industries that had been destroyed during the Civil War, to export products abroad and to purchase technologies that were necessary for the country’s industrialization. By 1927, with Harriman, Chiatura’s last concessionaire having left, the manganese of Chiatura had become an integral part of the Soviet economy.

According to Karl Marx, industrial enterprise is at the core of class conflict, involving two main groups: one represents capital or capitalists and the other is constituted of wage labor or wageworkers. The interests of these groups clash, which inevitably creates conflict and gives rise to antagonistic relations. At every stage of manganese mining in Chiatura, in historical contexts, this conflict has manifested itself and in this struggle the Chiatura miner has remained a paragon of an unconquered industrial worker. Through a lengthy process of strikes and resistance, the Chiatura miner has sought improved working conditions while also participating in revolutionary activities.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, ore mining at the Chiatura mines was halted until 2006, before the mines were privatized. This privatization involved the manganese mine, the ferroalloy plant in Zestafoni and the hydroelectric power station in Vartsikhe. The ferroalloys produced at the Zestafoni Ferroalloy Plant are made from manganese mined in Chiatura; in addition, a significant portion of the coal mined in Tkibuli is also utilized here. Both the Chiaturi mine and Zestafoni Ferroalloy Plant are owned by Georgian Manganese Holding Limited, a company owned by Georgian American Eloise, which in turn is owned by the ‘Privat’ group, including Ukrainian oligarch Kolomoisky whose name appears among its owners.

But let’s return to the strike and the striking miners. As previously mentioned, some of the miners remained in Chiatura, while others engaged in a hunger strike, and a few even sewed their mouths shut. A small group of the miners headed to Tbilisi and began protesting in front of the parliament building. They were joined by a small number of supporters including students, young people in the

Using hunger strikes and/or self-inflicted injuries, such as stitching up the mouth or eyes, as protest tactics have been highly debated in the past and continue to be so. In the previous article on this website, I discussed the importance of replacing self-harm with harm to the oppressor. The hunger strike by fellow miners, as well as the practice of sewing mouths and eyes shut, turned into a shot in the eye for the rest of the miners during a certain phase of their struggle. Seeing colleagues suffering due to starvation might lead them to accept conditions that otherwise no one would agree to. The plight of a starving friend can compel concessions. Therefore, the very nature of harm must change: self-inflicted damage should give way to harm inflicted upon the oppressor, causing them to experience financial losses due to an extended strike. This approach affects them most deeply. When the oppressor suffers losses, capitalists lose profits and are compelled to yield. Furthermore, the miners were aware that by prolonging the strike and creating a crisis in both Zestafoni and Chiatura, they would trigger a crisis throughout the entire production chain. To bring about such a crisis, time is required – precisely as long as it takes for the furnace at the Zestafoni plant to cool down.

Undoubtedly, daily concerns about the deteriorating health of their starving friends and colleagues prevented an indefinite extension of this process. At the same time, it is important to acknowledge the physical courage displayed by the miners through hunger strikes and

As previously mentioned, the long-term shutdown of mining activities in Chiatura, combined with the blockage of mined ore and export routes from the city, poses a threat to the Zestafoni ferroalloy plant. This presents a serious predicament for the company: disruptions in supply, financial losses, and production stoppage. Restarting production would incur multimillion-dollar costs. Anticipating this threat, the company, with the help of state media, launched a smear campaign against the miners, involving in the conflict united trade unions led by Irakli Petriashvili. He acted as the primary “buffer” for elites against workers’ discontent in Georgia, acclimatizing the workers to appallingly low standards of living, which is truly unusual for the region. Following lengthy negotiations, the miners agreed to

After the strike ended, Chiatura warmly embraced the miners who participated in hunger protests and rallies in front of the parliament in Tbilisi. Their physical strength, mental fortitude, and nerve have become emblematic of the struggle for a brighter future. This is exactly what is so much needed for this astonishingly beautiful yet ecologically threatened city, located on the Kvirila River which is now discolored to a somber black and where higher rates of cancer incidence are becoming evident.

The physical and intellectual bravery demonstrated by the miners constitutes two essential components that are necessary for Georgians to overcome feelings of humiliation and apprehension about the future. Transformation won’t arrive through humanitarian assistance or someone’s benevolence. It requires physical and intellectual courage, qualities that the miners have exemplified to the industrial working class and laborers in general – to those who, in spite of oppression and exploitation, stand steadfast on their feet and continue their fight.

Georgia will likely experience a wave of nationalism in the near future. However, we can assert with confidence that it will be bourgeois nationalism – a divisive force along national lines that creates the illusory notion of unity among antagonistic social classes within the nation. An alternative to this nationalism and its misleading perceptions can be found in the class dimension that socialist theory and practice, alongside the advanced segment of the working class, must cultivate.

Translated from Russian by Kun

Belarus

BelarusНапярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusOn the eve of the unknown the Belarusian writer is playing with the past

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusIm Angesicht der ungewissen Zukunft spielt eine belarussische Schriftstellerin mit der Vergangenheit

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusНакануне Неизвестного беларуская писательница играет с Прошлым

20 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaՌուսաստանն օգտագործել է Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի հակամարտությունը որպես իր աշխարհաքաղաքական շահերն առաջ մղելու սակարկության առարկա

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaRussia used the Karabakh conflict as a bargaining chip to advance its geopolitical interests

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaWie Russland im Spiel um seine eigenen geopolitischen Interessen den Berg-Karabach-Konflikt als Trumpf nutzte

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaКак карабахский конфликт стал разменной монетой в российских геополитических играх

12 December 2023 Georgia

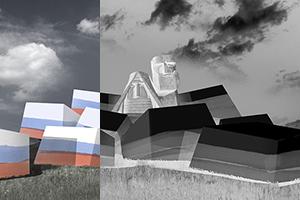

Georgiaამბავი ქართული პოსტკონსტრუქტივიზმისა

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaThe history of Georgian post-constructivism

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaDie Geschichte des georgischen Postkonstruktivismus

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaИстория грузинского постконструктивизма

11 December 2023