Belarus

BelarusЖыццё пад сталом

Напярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 © Alicyja H.

© Alicyja H.

This text could have been written by Artur P. or Viktor K. Or by Maria A., Olga D., Denis U., or by many other authors who thought they would never leave Belarus. But then Alyona M. heard a knock on her door and Maksim E. heard his doorbell ring. Yahor V. received a summons from the militia.

… This text Yahor V. compiled from his notes, correspondence, phone conversations, and symptoms.

Беларуская English Deutsch Русский

∗∗∗

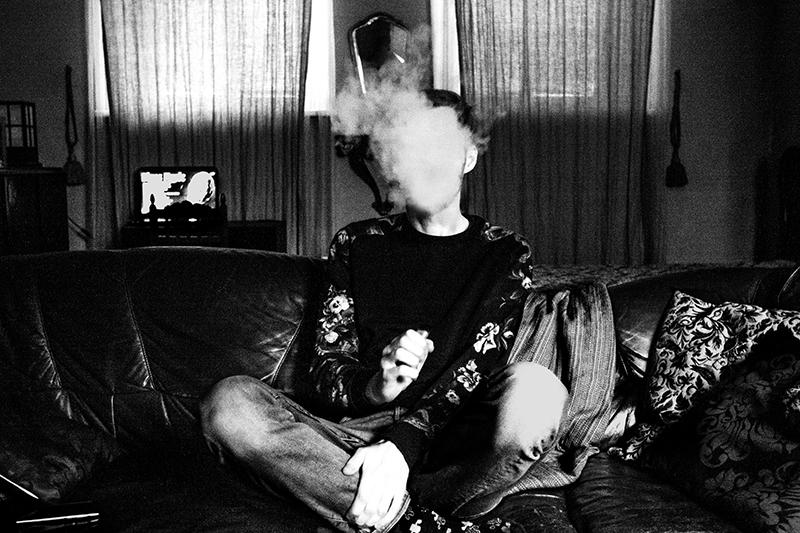

[inhale]

∗∗∗

It’s been a month that I am in Vilnius. How this came about, I can’t tell yet.

∗∗∗

“Are you alive there?”

“Alive but still don’t understand what I’m supposed to do here.”

I don’t have a job, just spending my last money. In Lithuania, I am an unnecessary person, I am unneeded. I am a fish thrown out of muddy water onto a warm clean shore.

∗∗∗

“Yahor, can you water the flowers? Those in the bedroom window, those big flowerpots on the floor beside the TV, and the little ones over the bar. You can use tap water at room temperature. I’d be very grateful to you.”

“Yes, no problem. By the way, I’ve found an apartment, moving in tomorrow.”

∗∗∗

“Did you sleep well in the new place? “

“I haven’t been sleeping well for the last couple of nights. I wake up at five at six and can’t sleep anymore. Some kind of a glitch in the program.”

“The trauma”.

∗∗∗

[inhale]

∗∗∗

It’s been a month that I am in Vilnius. But I can’t tell you how it came about.

∗∗∗

On the day of my departure I took some meat out of the freezer to defrost for dinner.

I was not planning to leave, although for the three preceding years it had been hard to live under the concrete slab that covered Belarus. I was only carried by the hope that injustice could not last so long. It seemed, then, at that very moment some hero would put everything right. But heroes kept disappearing one by one. Made of steel, they broke like dry branches. Who would have thought that such an ugly crooked structure could wreck so many lives?

Even Jesus, had he landed in Belarus, would have been found to be an extremist. He would have been accused of high treason and, possibly, sentenced to death, one more time.

∗∗∗

“Hi Yahor. On the tenth, Uncle Vasya was detained again.”

«Hi. I thought Vasya was hiding somewhere.”

“Misha has gone to Poznań.”

“And Vitalya, perhaps, to Georgia.”

∗∗∗

The conveyor belt of repression is moving so fast that I can’t say exactly if someone is dead, imprisoned, already out of the country, or not yet under arrest.

The conveyor belt of repression has been working for so long that I can’t remember when it was started up.

∗∗∗

In autumn 2020 I was woken a few times by the crunch of my own teeth. Such was my reaction to the gigabytes of violence around me. I was clenching my jaws so hard that broke two teeth in the end. I’d break a tooth, swallow it and be woken by pain. After the first such case, to my fear to live at daytime was added the fear to sleep at night.

This lasted for about two months. During the night my jaws would get so exhausted the next day I couldn’t eat solid food. I had stomach and eye problems. I didn’t want to see the outside world and couldn’t digest what I saw. At the same time, I understood that my problems were only minor. Nobody broke my spine, I didn’t suffer much, and, therefore, I probably didn’t have the right to tell my story thus interrupting others – the actual victims.

And after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine I completely lost the moral right to speak about myself. A broken man and a destroyed city are incomparable tragedies. I found myself outside the event horizon, alone with my misfortune.

This misfortune has not yet taken shape. It is constantly growing on all sides leaving me with no time or chance to realise what it is. It is millions separate unspoken misfortunes. There are no words to speak about it.

∗∗∗

“How is it going in Belarus? Is there anything you want to say to anyone here?”

”Say hello for me.”

∗∗∗

When things got unbearable, I would go to the forest. I would wander there for hours. The forest gave me shelter and a sense of security for a while. I intentionally chose paths leading to places where I would feel lost; I hoped that I wouldn’t be able to find a way back and that I would never return.

I remember, once I stood near some trees looking at the sky and trying to imagine I was a tree as well.

I wanted to live but I didn’t want to be a human being.

∗∗∗

“There’s a busik [translator’s note: slang term for a paddy wagon in Belarus] outside your house. I don’t know if they came for you or not.”

“And what are they doing there?”

“I’m not wearing glasses. Will text you later.”

“OK.”

“They’re cutting the trees. So that was a false alarm.”

∗∗∗

When the war began, a ban on visiting forests was introduced. Thus they took away my last opportunity to exhale. Since then, I only inhaled. Now I’m hurting on the inside, I feel I’m suffering from all diseases.

∗∗∗

I remember a friend of mine telling me, “If it doesn’t get worse, I can take it. It’s tolerable.” He went through a few “preventive conversations” and 24-hour detentions.

I knew sooner or later it would be my turn. I had a constant feeling that someone malicious is breathing down my neck.

My friend left Belarus two weeks before me.

∗∗∗

I seemed, outside Belarus I would at last be able to drop my shoulders, to shout, to weep my repressed emotions out. But I will probably always carry them with me.

Excuse me, what were you asking about?

∗∗∗

[inhale]

∗∗∗

Yes, I’ve been living in Vilnius for two months now.

There was not a single day that I wanted to go back home. I quickly accepted the fact that there was no home for me across the border (and books tell us about longing and nostalgia).

Exactly two months ago a lot of bad things happened to me. I still don’t want to stir up these memories. They are like a bag of dirty clothes, mine and somebody else’s. Maybe if no one touches it, it will somehow disappear?

∗∗∗

“What’s happened?”

“OMON [translator’s note: riot police], interrogation, polygraph, search.”

“Damn. Too bad. Will you tell me more?”

∗∗∗

“In the proceedings of the Investigation Department of the KGB of the Republic of Belarus is the criminal case ... instituted for an act of terrorism on the grounds of a crime under Part 1 Article 289 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus. The preliminary investigation revealed that …”

∗∗∗

“Hands on your knees, eyes on the floor. Got it?”

“Yes.”

“Can’t hear what you say. You got it?”

“Yes.”

“Your phone’s PIN?” “5008.”

“And those in my pocket are ulcer pills.”

∗∗∗

Later N, when he gets to know about it, will say:

“My God, they think they’ve found a criminal. Why?”

That will be the first time N has asked this question, I stopped looking for an answer as early as in 2020.

∗∗∗

They didn’t tell me why I was detained. I only knew that all the newspapers wrote about, all I had for so long been preparing for (but had never been ready), was already happening to me.

To me. How could this be?

∗∗∗

From newspaper headlines:

“In Bobruisk KGB agents detained an 18-years-old man. They stripped him of his clothes and made him, nude, talk about himself while they videoed him.”

∗∗∗

I was sure I fell into a trap for a long time. Like my great-grandfather who “remaining an implacable enemy of Soviet power, spread counter-revolutionary propaganda aimed at discrediting the Party. The troika of 11 November, 1937 ruled to put him into a correctional labour camp for 10 years.”

All that has already occurred both in the history of my country and in the history of my family. And now in my personal history.

I knew that no one would save me, neither the lawyers nor the resonance in the media. These institutions broke down. I was one on one with the evil with only strangers around me.

Perhaps, it was so much the better. At least no one would remember my fear. I wanted only one thing: to take the last breath of freedom. To detain it so that it would be inside me and never be breathed out.

“Detain” – this word can’t have other meanings anymore. It is forever only about man.

I thought, “That’s all.” From that moment, my body no longer belonged to me.

For a few hours, I kept my hands on my knees looking at the army boots of the riot policemen, knowing nothing about my future.

∗∗∗

“Why were you detained and then let go? Do you understand?”

“No.”

“That’s the most enigmatic part.”

∗∗∗

[inhale]

∗∗∗

I’ve been living in Vilnius for three months now.

Exactly three months ago I took some meat out of the freezer to defrost for dinner, and that same evening I was handcuffed on the Belarusian-Lithuanian border.

“Is that all? You only have a backpack? Put your hands behind your back. We're removing one passenger from the train.”

Handcuffs. How can this be possible?

∗∗∗

“It is 100% easier and freer for me in Ukraine under fire than it was for you in Belarus. I am not led around Ukraine in handcuffs.”

∗∗∗

Exactly three months ago I was handcuffed. In a few hours the handcuffs were removed. But within that short time, everything was broken. Quietly or even completely without sound broke everything that kept me from leaving Belarus.

∗∗∗

“Where are you heading next? You can go to Lithuania. Who told you, you couldn’t? Go. You know I have a feeling you won’t be coming back.”

∗∗∗

There was not a single day that I wanted to go back home.

I loved my home a lot. My father was born there. Portraits of my ancestors on the walls, a dresser made by my grandfather and restored by me in the corner. An old lamp under the ceiling – I brought it from Lviv. The doorknob I brought from Paris. One picture on the wall was embroidered by my mother, another – by my aunt, now deceased. Books autographed by writers on the shelves. I loved all things in this home. But I wonder if I’ll ever be able to wash them clean of other people’s hands. Will I be able, for example, to wash clean grandmother’s mirror so that I can look in it and not see an ugly me – weak, helpless, unable to defend himself, one who has in his own home to ask permission to come out to the porch to take a smoke, escorted by riot policemen with machine guns. Things that used to tell me about my travels and my family now will always remind me about something I will not want to keep in my memory.

Some émigrés write they are homesick, but I’m not. All my love turned into vinegar. I have no home.

∗∗∗

“Yahor, start talking. This will be such a joy for the people.”

∗∗∗

Well I don’t know. Frankly, I want to keep silent along with them. I have no hope to be understood by someone outside, anyway.

∗∗∗

[instead of exhaling]

∗∗∗

Vilnius is a beautiful city.

The only bad place is the bus station. When I see passengers fill a coach to Minsk I find myself struggling to hold back tears. This is not homesickness, this is the fear to be on this coach and hear a voice from behind saying, “Yegor Ivanovich, follow us.”

People do not just get on a coach; they fall silent and disappear in it.

One of these days I put a friend on this coach.

She returned to Belarus to try to live there once again. Without protection and without an army. One on one with a big evil. Without any power to resist it. Battered and smashed from the inside. Without any fault of hers (but with the obligation to carry on her broken back the sense of guilt because, “Right now, killers are flying to my Kyiv from your territory”). Scared. Whitened by what she saw. Frozen by the inability to endure the pain. With one sole desire: to survive the evil and maybe protect something alive with her hand.

And, you know, she can.

Translated from Russian by Alexander Stoliarchuk

Belarus

BelarusНапярэдадні Невядомага беларуская пісьменніца гуляецца з Мінулым

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusOn the eve of the unknown the Belarusian writer is playing with the past

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusIm Angesicht der ungewissen Zukunft spielt eine belarussische Schriftstellerin mit der Vergangenheit

20 December 2023 Belarus

BelarusНакануне Неизвестного беларуская писательница играет с Прошлым

20 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaՌուսաստանն օգտագործել է Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի հակամարտությունը որպես իր աշխարհաքաղաքական շահերն առաջ մղելու սակարկության առարկա

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaRussia used the Karabakh conflict as a bargaining chip to advance its geopolitical interests

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaWie Russland im Spiel um seine eigenen geopolitischen Interessen den Berg-Karabach-Konflikt als Trumpf nutzte

12 December 2023 Armenia

ArmeniaКак карабахский конфликт стал разменной монетой в российских геополитических играх

12 December 2023 Georgia

Georgiaამბავი ქართული პოსტკონსტრუქტივიზმისა

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaThe history of Georgian post-constructivism

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaDie Geschichte des georgischen Postkonstruktivismus

11 December 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaИстория грузинского постконструктивизма

11 December 2023