Moldova

MoldovaCine-i șefu’ aici?

Ce se întâmplă cu Biserica Ortodoxă din Moldova

4 December 2023 Film still from SERGO GOTORANI© Veli

Film still from SERGO GOTORANI© Veli

After the oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili and his Georgian Dream party came to power, restrictions on freedoms were introduced into various aspects of political and public life. These restrictions had a particularly painful impact on Georgia’s cultural sphere. Cultural institutions that were once independent such as the National Book Center, the Writer’s House, the National Film Center and the National Museum have, one by one, fallen under control of the ruling party. Literary scholar Irina Beridze discusses the evolution of Georgian cinema over the years of independence and liberation from censorship, as well as the challenges cinema faces again with the looming threat to freedom of expression.

ქართული English Русский

A new Georgian cinema began to take shape in the early 1990s, when the young republic on the outskirts of the collapsed Soviet empire embarked upon a route of autonomous political and cultural development. The civil war in Tbilisi

In the wake of the Soviet Union’s disintegration, the Georgian film sector grappled with a crisis brought about by a dramatic departure from the centralized Soviet film production system and the unanticipated release from censorship.

Film still from ZGVARZE© Georgian National Film Center

Film still from ZGVARZE© Georgian National Film CenterA few of the following examples support the argument that, despite political instability, Georgian filmmakers still managed to lay the foundations of a new Georgian arthouse and experimental cinema. These examples include the films by Dito Tsintsadze, who emigrated to Germany during the war in Abkhazia. He made his debut short feature film, STUMREBI (Guests), in 1991 and subsequently received the Silver Leopard at the Locarno Film Festival for the film ZGVARZE (At the Limit, 1993), which revolves around the brewing civil war in Georgia. Many of ZGVARZE’s characters will, in real life, perish in the forthcoming Abkhazia war, while some of their lives will be saved due to their involvement in the filmmaking process. As the director explained in an interview, “Filming was easy since no one was really acting.” Furthermore, the war compelled quite a pragmatic approach to cinematic aesthetics. The alternating use of color and black-and-white frames was born out of sheer necessity due to a lack of film stock. Tsintsadze’s film marks a departure from the conventions of Soviet cinema. The allegorical and poetic language gives way to a thorough analysis of specific and pressing topics, presented in a hybrid format that blends fiction and documentary elements. As Tsintsadze himself stated, “Georgian cinema used to be filled with humor and poetry. We introduced entirely different themes — much harsher and bloodier. The films became tougher, addressing issues that had never been discussed before.” (Dito Tsintsadze).

Film still from ARA, MEGOBARO© Georgian National Film Center

Film still from ARA, MEGOBARO© Georgian National Film CenterAnother innovative work is the short feature film ARA, MEGOBARO (No, my friend) by Gio Mgeladze. Completed in 1993 and filmed in an amateur style, the movie tells the story of young people from Tbilisi who succumb to gang

During this period films primarily delve into the issues of individual demoralization, isolation, and alienation, reflecting the chaos faced by the young independent state. Georgian cinema of this era is dominated by criminal gangs and drug mafias, themes that are intertwined with newly emerging religious and ethnographic motifs.

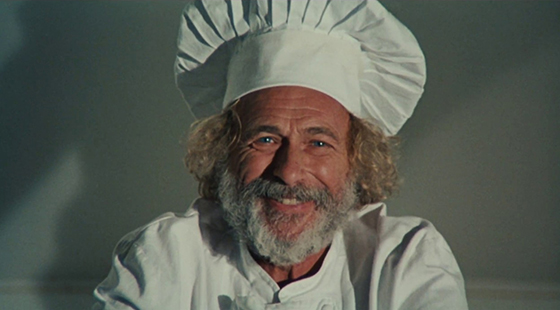

Film still from SHEKVAREBULI KULINARIS 1001 RECEPTI© Les Films Du Rivage

Film still from SHEKVAREBULI KULINARIS 1001 RECEPTI© Les Films Du RivageThe same historical period, however, ushered in the first international successes for Georgian films. For instance, the feature film by Temur Babluani UDZINARTA MZE (The Sun of the Sleepless, 1992) was awarded the Silver Bear at the Berlinale in 1993. Lana Gogoberidze also directed her first

At the same time, the Georgian director Nana Dzhordzhadze made a joint Georgian-French film titled SHEKVAREBULI KULINARIS 1001 RECEPTI (A Chef in Love, 1996). This was the first picture from independent Georgia to be nominated for an Oscar. Back in Soviet times Nana Dzhordzhadze made significant contributions to the resistance against Soviet censorship. Her film MOGZAUROBA SOPOTSHI (The Journey to Sopot, 1980) was banned by the censors, released seven years later and was first screened at the Oberhausen Film Festival in 1987. Dzhordzhadze’s

In the 2000s a new film institution emerged in Tbilisi, marking the end of over a decade of stagnation in the Georgian film industry. In 2001, the Georgian National Film Center was established under the Ministry of Culture and Monument Protection of Georgia. As a legal entity of public law, the center is supposed to determine state policy in the field of cinematography and provide government support for the advancement of new Georgian cinema. Differing from the Soviet and

The hybrid genre of fiction-documentary film has become a distinctive hallmark of Georgian cinema. One of the notable exemplars of this genre is the film SERGO GOTORANI (Sergo the Rogue), directed, written, and produced by Irakli Paniashvili. The film presents the story of a Georgian refugee family from Abkhazia struggling to survive in a garbage dumping ground. The film had its premiere at the Tbilisi International Film Festival in 2009 and garnered positive reviews from critics in Georgia. However, it remained largely unnoticed by the broader audience, which can be attributed in part to its experimental form and visual language. The

During the early 2000s, the first international film festivals began to emerge in Georgia. The Tbilisi Film Festival, which initially had limited financial resources, later received support from the Georgian Film Center and the Ministry of Culture, ultimately becoming the largest film festival in Georgia. In 2006, the Batumi International Arthouse Film Festival (BIAFF) was founded and is now held annually in September on the Black Sea coast. It carries forward the traditions of Black Sea movie festivals, such as the ones in Odessa and Varna. Since 2013, Tbilisi has hosted CinéDOC-Tbilisi — the first international documentary film festival in the South Caucasus. The festival aims to promote the “creation of a strong regional identity in the South Caucasus, rooted in shared history and cultural values”. Under the competition section Focus Caucasus and the pitching platform New Talents Caucasus, a unique creative environment has been established to encourage collaboration among filmmakers from Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia.

The 2008 war between Russia and Georgia generated a new crisis in the Georgian film industry, which it was only able to overcome a few years later. Speaking of the dynamics of film decolonization in

In 2003, the ‘Rose Revolution’ resulted in a change of political power in Georgia. While the new liberal democratic system successfully navigated past the

Film still from MILSADENIS MEZOBLEBI© ARTE France 4

Film still from MILSADENIS MEZOBLEBI© ARTE France 4The central figure in the new wave of Georgian cinema is the Georgian-French director and actress Nino Kirtadze. After completing her literary studies in Tbilisi in the 1990s, she initially worked as a reporter, covering the wars in the Caucasus. During this period, she also appeared in films by Nana Dzhordzhadze. In 1997, Kirtadze emigrated to France and in 2000 she made her directorial debut with a film about Eduard Shevardnadze titled, “Les trois vies d’Edouard Chevardnadze” (The Three Lives of Eduard Shevardnadze). This was followed by her documentaries Chechen Lullaby (2001) and MILSADENIS MEZOBLEBI (The Pipeline Next Door, 2005), a film that focused on the construction of the ‘New Silk Road’ — the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline passing through the resort area of Borjomi Valley in Georgia. The documentary portrays a rural community in direct conflict with the interests of the major international oil corporation BP and the logic of capital. Kirtadze’s work has marked the inception of a tradition of Georgian environmental cinema.

Film still from DADUMEBULEBI© Salomé Jashi

Film still from DADUMEBULEBI© Salomé JashiSimultaneously, the first short documentaries of Salomé Jashi made their debut. Her introduction to this

Film still from ALTZANEY© Artefact Production

Film still from ALTZANEY© Artefact ProductionIn 2008, Georgian producer and documentary director Nino Orjonikidze established the production company Artefact Production. She obtained international recognition after the collaborative 2009 film ALTZANEY, created with Vano Arsenishvili, was presented at the DOK festival in Leipzig in 2009 and at the Krakow Film Festival in 2010. Currently, Nino Ordzhonikidze teaches experimental and documentary film in Tbilisi and oversees the multimedia platform Chai Khana. This platform produces multilingual short films with a specific focus on the South Caucasus. Her 2012 film, INGLISURIS MASTSAVLEBELI (English Teacher), serves as a commentary on the former President Saakashvili’s nationwide ‘linguistic revolution’ initiative, in which he attempted to attract foreign English teachers to rural Georgian regions as part of a modernization project. The film highlights the disparity between this initiative and the actual realities of life in rural Georgia. In GVIRABI (A Tunnel, 2019), Nino Orjonikidze and Vano Arsenishvili chronicle the large infrastructure project ‘New Silk Road’ (see above: Nino Kirtadze), which is designed to connect China and Western Europe passing through the territory of Georgia. The road project poses a threat to peripheral spaces and ecosystems of the country. Once again, the film highlights the conflict between the interests of global capital and the living environment of Georgian farmers in remote areas.

Amidst an ongoing period of still fragile democracy, another change of power occurred in 2012, which subsequently brought about some shifts in the cultural and political dynamics of the Georgian film industry. Over this period, the National Film Center established itself as the primary institutional structure and the only fundamental support system for new Georgian cinema. However, the Center in Tbilisi continues to operate under the direct authority of the Georgian Ministry of Culture, which retains the autonomy to appoint its director. Presently, the center is fighting to obtain an independent institutional status. In March 2023, Gaga Chkheidze, the

Film still from MOTVINIEREBA© Mira Film, CORSO Film, Sakdoc Film

Film still from MOTVINIEREBA© Mira Film, CORSO Film, Sakdoc FilmThis process was set in motion last year, spurred by the international acclaim garnered by the documentary MOTVINIEREBA, (Taming the Garden, 2021) by Salomé Jashi. The film was featured at the Forum section of the Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale), had its premiere at the Sundance film festival, and earned a nomination for the European Film Award. MOTVINIEREBA documents the ambitious undertaking of Georgia's wealthiest individual, Bidzina Ivanishvili, to establish an exotic garden on the western Georgian Black Sea coast. Ivanishvili buys up

Salomé Jashi's critique of the de facto ruler of Georgia led to the swift cancellation of her film’s screenings at the Tbilisi House of Cinema, ordered by Mindia Esadze, the director of the Georgian Film Academy.

The incident prompted strong reactions from the Georgian film industry and the Georgian PEN Center, both of which determined it to be alarming and pronounced it the first instance of censorship in the history of independent Georgia. In a show of solidarity with the director, a few movie theaters and cultural venues organized impromptu public screenings of the film. The state’s attempts at taming Georgian culture and cinema have resurfaced after a

In November 2022, Georgian documentarians created a new platform called DOCA (Documentary Association Georgia). The platform is designed to consolidate filmmakers and give birth to the first independent structures outside the state-controlled Film Center in the future. As outlined in their mandate: “DOCA Georgia works for the independence, accessibility, transparency and viability of the film industry in the country.”

Today, new Georgian documentary cinema is stronger than ever. However, the pivotal struggle for the independence of Georgian cinema is still far from over.

Translated from Russian by Kun

Moldova

MoldovaCe se întâmplă cu Biserica Ortodoxă din Moldova

4 December 2023 Moldova

MoldovaWhat is going on with the Moldovan Orthodox Church

4 December 2023 Moldova

MoldovaWas in der Moldauisch-Orthodoxen Kirche gerade vor sich geht

4 December 2023 Moldova

MoldovaЧто происходит с Православной церковью Молдовы

4 December 2023 Georgia

Georgiaქართული პოლიტიკური მართლმადიდებლობა და რუსეთი

28 November 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaGeorgian “political Orthodoxy” and Russia

28 November 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaGeorgiens „politische Rechtgläubigkeit“ und Russland

28 November 2023 Georgia

GeorgiaГрузинское «политическое православие» и Россия

28 November 2023 Belarus

BelarusЦі могуць беларусы крытыкаваць палітыку Захада?

22 November 2023 Belarus

BelarusCan Belarusians critisise Western policies?

22 November 2023 Belarus

BelarusDürfen Belarussen den Westen kritisieren?

22 November 2023 Belarus

BelarusМогут ли беларусы критиковать политику Запада?

22 November 2023